[D]UBLIN, Ireland — Browse most any bookstore in this Celtic city and, amid biographies of mythic local man upon mythic local man, you’ll find a history or two about a 19th-century American woman named Asenath Hatch Nicholson.

“In Ireland she is best remembered for her sympathetic depictions of the country and its people on the eve of and during the Great Famine, which she witnessed firsthand,” University College Dublin professor emeritus Cormac O’Grada says. “She deserves to be better known in the U.S. for her support of progressive causes.”

But that’s a challenge when even residents of her home state of Vermont can’t identify her.

Turn to Irish scholars, however, and they’ll expound on a pioneering Green Mountain State woman who, traveling the Emerald Isle alone on foot, wrote two books: “Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger; or an Excursion Through Ireland, in 1844 & 1845, for the Purpose of Personally Investigating the Condition of the Poor” and “Annals of the Famine in Ireland, in 1847, 1848, and 1849.”

“Should I sleep the sleep of death, with my head pillowed upon this wall, no matter,” she penned in 1844 while resting her blistered feet on a roadside. “Let the passer-by inscribe my epitaph upon this stone, fanatic, what then? It shall only be a memento that one in a foreign land loved and pitied Ireland and did what she could to seek out its condition.”

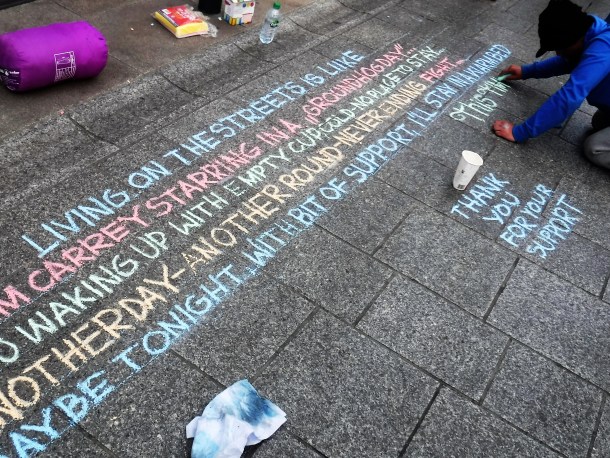

Tuesday will mark the 25th anniversary of the United Nations declaring Oct. 17 as the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. Commemorations set to take place worldwide — including at Dublin’s Famine Memorial — call for “discovering or sharing stories to promote dialogue and understanding.”

“In her private life, Nicholson had an evangelical belief in the moral and social reform of all classes,” says Christine Kinealy, director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Connecticut’s Quinnipiac University. “For her, lifestyle was an essential part of this reform. She was an advocate of the benefits of a simple diet, regular exercise and occasional fasting. And she became a champion of the vegetarian, coffee-free regime developed by Rev. Sylvester Graham (of the cracker fame), who became a personal friend.”

Nicholson’s boardinghouses also promoted temperance and abolitionism, with some historians speculating that the American Anti-Slavery Society originated there. As the latter issue began to split the nation, the United States saw a wave of Irish immigrants who, by the 1840s, comprised nearly half of all newcomers.

“It was in the garrets and cellars of New York that I first became acquainted with the Irish peasantry,” the Vermonter wrote, “and it was there I saw that they were a suffering people.”

Widowed and arthritic at age 52, Nicholson nevertheless sailed to Ireland in the spring of 1844 “to personally investigate the condition of the Irish poor.”

But while those men came and went in a matter of weeks, Nicholson spent years walking the country, and did so at a time when a woman — especially one in a polka-dot coat, bonnet, bearskin muff and rubber boots — was mistaken as poor, crazy or, in one case, a man in disguise “come to do some great mischief.”

Nicholson knew better.

“I was,” she wrote, “days and weeks in the wildest parts, much better attired than they were.”

Singing hymns while strolling through all but one Irish county, Nicholson inspected workhouses in the cities and stayed at poor people’s homes in the country, sharing such favorite Bible verses as John 14:2 (“My Father’s house has many rooms”) and Hebrews 13:2 (“Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it.”).

Nicholson traveled for 15 months, then returned in 1846 for a second tour. This time she didn’t simply observe but also distributed food in soup kitchens and on the street to feed those starving from a nationwide potato blight.

The face of famine, she discovered, was “misery without a mask.”

“Hunger and idleness have left them a prey to every immorality; and if they do not soon practice every vice attendant on such a state of things, it will be because they have not the power,” she wrote. “Human nature is coming forth in every deformity that she can put, while in the flesh; and should I stay in Ireland six month longer, I shall not be astonished at seeing any deeds of wickedness performed, even by those who one year ago might apparently have been as free from guilt as any among us.”

“Nicholson’s sympathy for the Irish poor, both within Ireland and in the United States, was in marked contrast to contemporary orthodoxies,” Kinealy notes. “Unusually, she did not believe that the poor were to blame for their own poverty.”

Instead, the Vermonter publicly criticized government officials, clergymen and relief volunteers she considered self-serving.

“By the standards of her time,” O’Grada observes, “Nicholson’s views were progressive, democratic, and compassionate.”

Nicholson returned to the United States in 1852 and died of typhoid fever in 1855. She is buried in an unmarked grave in Brooklyn. Her name nonetheless can be found on the covers of her two books, recently rereleased by Hofstra University professor Maureen O’Rourke Murphy, author of the biography “Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine.”

“The austerity of her childhood on the Vermont frontier prepared her for the hardships of her travel through Ireland,” Murphy writes of Nicholson. “She not only recorded that history, but also helped to shape the history of those years.”

The New York Tribune asserted that in her 1855 obituary.

“By unusual diligence, self-denial, benevolence and frugality, she has been enabled to accomplish great good,” the newspaper concluded, “but has left little behind her but the rich legacy of her Christian example and valuable writings.”

Writings that, two centuries later, still resonate.