.

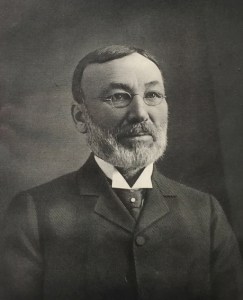

[I]f Vermont ever had an Ebenezer Scrooge, it was Silas L. Griffith.

Griffith made his fortune by taking advantage of other people’s misfortune. He bought up huge tracts of land, much of it through foreclosure. He eventually amassed 50,000 acres that sprawled over the towns of Danby, Mount Tabor, Dorset, Arlington, Peru, Manchester, Wallingford and Groton.

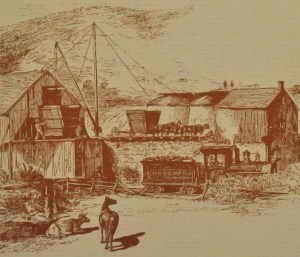

He had nine sawmills constructed around his vast holdings so timber had to be hauled only relatively short distances. He had a sawmill built in a part of Mount Tabor that soon became known as Griffith. A small community sprang up around the mill and eventually encompassed 40 to 50 structures, including a large boardinghouse for single men, cottages for married men and their families, a blacksmith shop, harness shop, wagon shop, schoolhouse, general store and stables. Similar, though smaller, communities grew up around the other mills.

Efficiency was the key word in Griffith’s enterprises. To connect his sprawling empire, Griffith had what are believed to be the first telephone lines installed in Vermont, strung between the main office and each sawmill.

Reducing and reusing byproducts and waste was a way to increase profits. He insisted loggers use saws instead of axes to reduce the amount of wood wasted in felling trees. His sawmills produced great mounds of sawdust, which he sold to ice houses to keep the ice cold.

And he saw great potential in the bits of wood that were too small to be turned into lumber.

Griffith hit on the idea of converting the scraps into charcoal. Over time, he had workers build three dozen large brick kilns in clusters at job sites in Danby and Mount Tabor. The kilns stood 25 to 30 feet in diameter and rose 12 feet. They converted as much as 20,000 cords of wood into 1 million bushels of charcoal annually. The charcoal operations helped feed factories around the Northeast and made Griffith fabulously wealthy.

If Griffith found every way he could to squeeze more money from his land, he did the same with his employees. He refused to let workers wear watches. He didn’t want them complaining they were being overworked. But Griffith insisted his employees loved their labors. He told a writer for Outing magazine in 1885: “(T)hey lead a life of excitement and, to them, one of pleasure. They go to work as early as it is light enough for them to see, and chop until dark …”

Griffith’s workers were expected to shop for their basic needs at one of the company’s six general stores. “By the time they got their work done,” said Bradley Bender, president of the Mount Tabor-Danby Historical Society, “they had pretty much paid for their food and clothing.”

Loggers and mill workers didn’t get rich in Griffith’s employ. In fact, some workers fell into debt to him. Bender told of a worker who quit his job at one of the mills. Walking away from the site, he was intercepted by Griffith, who asked the man what he was doing. Quitting, he replied. Then Griffith reminded the man of his unpaid bills, apparently including the purchase of his pants, which Griffith made the man remove and hand over on the spot.

Griffith was no more sentimental about his first marriage. After 20-some years of marriage, Elizabeth Staples, who bore Griffith four children, sued for divorce when she learned he had been having an affair with his secretary. When Griffith remarried, this time to the much younger Katherine Tiel, a distant cousin who was a Philadelphia socialite, his new wife refused to live in the house he had shared with Elizabeth. Griffith had the house torn down and a new one built on the same footprint. He had the lumber from the first house carried to a nearby kiln and converted into charcoal.

All this slashing and burning, and profit making, apparently couldn’t keep Griffith from wondering whether that was all there was to life. For all his financial success, Griffith suffered a series of personal tragedies. First, his daughter Lottie died at the age of 7 weeks. Ten years later, his daughter Agatha died before she turned 2. And some years later, his son, Harry, died at age 10.

Like Scrooge — perhaps minus the ghostly visitations — Griffith decided to become more generous. He donated a library to the town — the S.L. Griffith Memorial Library serves Danby today — and started giving clothes and gifts to workers’ children at Christmas.

Upon the deaths of Griffith and his wife, their wills established a clothing and gift fund. To this day, the children of Danby and Mount Tabor, ages 2 to 12, receive presents courtesy of the Griffiths. Each year children and their families crowd into the Congregational church and listen to carols and a homily. All the while, children study the pile of presents beneath the large Christmas tree up front. The gifts aren’t wrapped, as has apparently always been the tradition.

“You sit in the pews and see the gifts and you don’t really know which one is yours,” says Cher Powers, who grew up locally and now coordinates the event. “I was just remembering one year when I was looking at the presents and hoping the baby doll was for me.”

After an adult finishes explaining the tradition and who Griffith was, the children have their names called, one by one, and they are given their presents. With the gifts comes a vestige of the 19th century — each child is also given candy and an orange, which were once rare and expensive treats that were part of the tradition as Griffith envisioned it.

This year, on Dec. 20, more than 150 children will receive gifts. Griffith originally gave gifts only to children in the sections of Danby and Mount Tabor where his workers made up the entire population. But organizers recently changed the tradition. Now all the towns’ children receive gifts.

The tradition ties the communities together in shared celebration, and it unites the generations. Having grown up with the tradition, Powers says, “I know what it was like to be on the other side too. I understand the kids’ anxiousness and how important this is to them.”

Rather than have children submit wish lists, as might have been done in Griffith’s day, Powers and her sister Chelley Tifft use a more modern technique. They reach out to parents with text messages to learn what children might like.

Griffith’s endowment has grown over the years. “We’ve done very well with the trust, so we can spend a lot of money,” Powers says. A sizable gift can come in handy sometimes. “For some of the kids, this is still one of the biggest gifts they will get,” she says.

Griffith’s business empire is long gone. It shut down shortly after his death in 1903. Years of endless cutting had left the hillsides bare. If not for his generosity to the town of Danby and to the area’s children, all that would remain today of his work would be some cellar holes, mounds of sawdust and scatterings of bricks.

Eventually, however, Griffith apparently realized that there was more to life than money and, like Dickens’ character, sought to redeem himself.