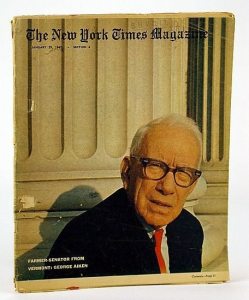

When George Aiken shopped his hometown Putney Co-op in 1968, he could buy a candy bar for a nickel, a can of soup for a dime, a loaf of bread for a quarter and a gallon of milk for a dollar. But Vermont’s late, legendary U.S. senator reported an even bigger bargain that year.

His $17.09 re-election campaign.

Sick of all the political ads and paraphernalia that have spurred Aiken’s successor, Patrick Leahy, to raise nearly $5 million to defend his position this year? Rewind for a moment to the summer of 1968, when the message was scorching but the medium was as simple as some 6-cent postage stamps, a tank of gas and a few phone calls.

Aiken, the state’s U.S. senator since 1940, was up for re-election that fall. For the first time since that first win, he faced a primary challenge. But five days before the Aug. 1, 1968, deadline to place names on the ballot, he had yet to say anything.

Aiken, born in 1892, was a horticulturist who became a Putney School Board member in 1920, Vermont legislator in 1930, speaker of the house in 1933, lieutenant governor in 1934 and governor in 1936. He first won his U.S. Senate seat in 1940 after a bruising Republican primary contest. After that, he was re-elected again and again with little said or spent.

A Bethel man named William Tufts hoped to change that. On May 21, 1968, he announced his intention to challenge the U.S. Senate’s ranking Republican in the party’s primary that September.

The conservative Tufts despised the moderate Aiken, who two years earlier made the most famous speech of his career, a 12-minute message that reporters summed up in one sentence: “President Johnson should declare victory in Vietnam and get out.”

Tufts instead wanted Aiken out.

“If he doesn’t retire voluntarily,” Tufts said, “I believe the people will retire my opponent because of his age.”

Aiken would turn 76 that August (the same age Leahy is today) and be 82 at the end of the next term in 1975. Would he retire? Would he run? Days before the deadline to place names on the ballot, he had yet to say.

‘Never made a formal announcement’

“He has a phobia about things that are normal for politicians,” then Rutland Herald reporter Stephen Terry wrote at the time. “He has never made a formal announcement. His name has just appeared on the ballot after friends from the Windham County area have gathered the necessary 500 signatures needed on the petitions for the primary elections.”

That happened again in 1968. Four days before the deadline, Aiken’s friends filed nearly 2,500 signatures — five times the requirement — with upward of 400 supporters from his opponent’s home turf.

What wasn’t reported at the time was the fact Aiken almost retired that year.

“The only reason he ran again was because his friend Mike Mansfield asked him to,” says Terry, who today is a political analyst for Burlington television station WCAX.

Mansfield, a Democratic senator from Montana, was majority leader. He didn’t want to serve without Aiken, his longtime breakfast partner in the Senate dining room, Terry learned years later.

Aiken’s opponent, for his part, was hungry. Tufts charged the incumbent had the support of “Communists, radicals and other left-wing extremists.” He called himself the David who would slay Goliath, using Aiken’s age as the stone in his slingshot.

Aiken didn’t hurl anything back. He was busy in Washington, arriving to work at 6:45 each morning and leaving no earlier than 6 p.m. (except Saturdays, when he stopped at noon.)

Vermont’s congressional delegation currently boasts dozens of outposts and aides. Aiken, however, had only his capitol office and a staff of 10, the smallest of any senator. On June 30, 1967, he made news with further cost cutting at the end of the fiscal year:

“FT. MYERS, Va. – U.S. Sen. George D. Aiken, R-Vt., Friday morning married Miss Lola Pierotti, his chief aide for the past 30 years. Then he fired her. The new Mrs. Aiken will continue to work for the Senate Republican dean as an unpaid employee.”

‘Better than getting on television’

Before her death in 2014 at age 102, Lola Aiken would refer to her husband as “the governor” since he believed that was better than being one of 100 U.S. senators. She credited his work ethic for his electoral success.

“People called the governor direct — there was never any in-between,” she once told this writer. “Also, if you couldn’t answer a letter within 24 hours, you wrote an acknowledgement and said we’ll get back to you as quick as we can. An awful lot of people had good service from our office. They’d tell their family, they’d tell their friends. That’s better than getting on television suddenly at the end of a campaign and spending a lot of money.”

Aiken shunned pins, bumper stickers, signs and television commercials. Instead, he tried something different in 1968: One week of campaigning.

That summer, Aiken went to Montpelier for a courtesy call to Gov. Philip Hoff — the first Democrat elected to the post in modern Vermont history — before visiting six counties in six days.

The schedule:

Tuesday: Lunch in Island Pond to discuss plans and problems of that area.

Wednesday: Dinner in Stowe to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Blue Seal Feeds.

Thursday: Guest of the Association at Magic Mountain to honor expansion of skiing development there.

Friday: A meeting in White River Junction to open a new Howard Johnson motel.

Saturday: Old Home Day in Rupert.

Sunday: Dedication of the new Central Vermont Hospital in Berlin.

“His way of campaigning would be to just stop off and visit folks,” Terry remembers. “One of his favorite things was to walk down the street in a Vermont town and talk.”

Tufts was a vocal Mormon, and he often tripped up on the trail, Terry says.

“I asked Tufts, ‘Why are you running against Sen. Aiken?’” Terry recalls. “He said, ‘I’m running against Sen. Aiken because God told me to.’ I asked him again. And he told me again. That next day we had a big headline, ‘Tufts Says God Told Him to Run Against Aiken.’ At that time, candidates did not talk about religion or their personal beliefs, and those who did were viewed as somewhat odd. Mr. Tufts quickly fell in that category.”

‘Early version of Bernie Sanders’

The clincher came at a rally in Jericho.

“The candidates had to get up on a hay wagon,” Terry continues. “Sen. Aiken was on the wagon, and Bill Tufts was climbing up when it started to rock and tip. George Aiken very calmly said, ‘This is not the time to rock the boat.’ Everybody clapped. It was one of those phrases that just captured the moment.”

On Sept. 10, 1968, Aiken beat Tufts with almost 75 percent of the vote. Ten days later, they filed campaign finance reports with the Vermont secretary of state. Tufts spent $2,466.33. Aiken recorded $17.09. (A ratio of 144-1.)

In her later years, Lola Aiken would laugh as she told one last story about her husband’s last campaign. It seems the chairman of the rival Vermont Democratic Party had asked her to mail him petitions so he could help put the lifelong Republican’s name on the ballot.

“The governor gave me hell, because that went into that $17.09,” Lola Aiken would recall. “He said to me, ‘If you hadn’t sent the petitions but had told him to go to Montpelier and get them, I would have spent less!’”

With no Democratic opposition, George Aiken coasted to victory that November. He served his six-year term, then retired to Putney, where he died Nov. 19, 1984.

Terry left his reporter’s job in 1969 to work in Aiken’s office.

“As far as I’m concerned, Aiken’s real memory ought to be his work on Vietnam in the Foreign Relations Committee and being a champion for rural America,” Terry says. “But what that $17.09 means is he was very suspicious of big money in politics. Aiken was always critical of people and corporations who gave large amounts to candidates. On that issue, he was an early version of Bernie Sanders.”

Aiken has been a memory for 32 years, but his legend just grows larger.

“We mythologize certain figures as a way of understanding and ordering our own lives and society,” retired state Archivist D. Gregory Sanford writes in the book, “The Political Legacy of George D. Aiken.” “The degree to which we feel alienated from our present is often expressed in the degree we mythologize and idealize our past.”

Sanford has added up every penny of Aiken’s campaign spending from his first statewide race for lieutenant governor in 1934 to his last U.S. senate run in 1968. The grand total: $4,423 and 3 cents.

“Here’s the quintessential Vermonter who was in office for 50 years of the 20th century, and to achieve all those offices he spent a total of 4,000 bucks,” Sanford says. “It’s less about mythology than a current wistfulness. This may get me in trouble, but Leahy has been in office longer than Aiken — why do you need millions of dollars?”