[T]he Addison County Fair and Field Days will no longer allow the sale of Confederate flag merchandise.

The change in policy was announced Monday after a petition drive by the Champlain Valley Unitarian Universalist Society gathered more than 600 signatures in one week.

Members of the church had written to the fair’s directors the previous week and were invited to a board meeting Monday. At the meeting, congregants Piper Harrell and Theresa Gleason presented the petition and explained why they’d launched it.

“I have friends who told me, ‘I won’t attend this fair,’” Harrell said Thursday. That informed the case she and Gleason made before the board. It wasn’t a Civil War history lesson, according to Harrell. “It was about the fact that there are people in this community who literally do not feel welcome.”

According to Harrell, board members were very receptive, and they had a positive conversation.

“We both agreed that what we wanted was to have a civilized discourse,” said Harrell. “That was as important as anything else.”

Members of the board did not return calls for comment. This year’s fair starts Tuesday and runs through Aug. 13.

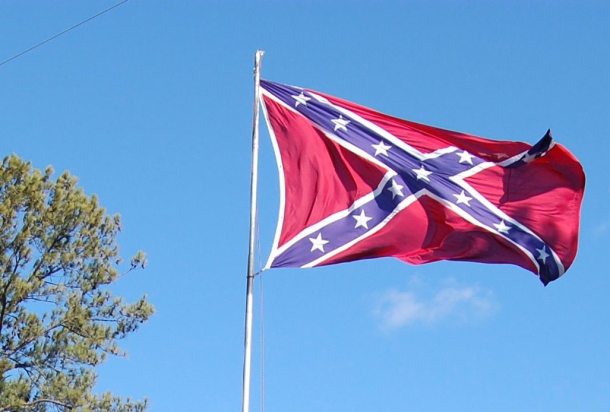

The Addison County fair dates back to the mid-1800s and is the state’s largest agricultural fair. The weeklong event includes a demolition derby, pony- and ox-pulling competitions, and a popular petting zoo. For years one of the booths at the fair has sold only Confederate flag merchandise.

“It’s been really offensive,” said Harrell. “We’ve all seen it. It’s pretty obvious.”

Vendors at county and state fairs often travel up and down the Eastern seaboard attending events and selling their merchandise, said Tim Shea, executive director of the Champlain Valley Fair. Shea said the Champlain Valley Fair doesn’t have a written policy on Confederate flag merchandise but vendors selling items like T-shirts bearing the symbol are asked to take them down. Shea said he’s never had problems with vendors complying.

Fernand Gagne, chairman of the Franklin County Field Days, said he’s never encountered Confederate flag merchandise at the fair and that it doesn’t have a written policy on the issue.

Last year the issue surfaced at the Vermont State Fair in Rutland, said Luey Clough, president of the Rutland County Agricultural Society, which manages the event. There were complaints that some of the vendors were selling Confederate flag merchandise along with other items. As a courtesy, he said, fair organizers notified the vendors, but the board decided that since it wasn’t a legal issue, members didn’t have the authority to tell vendors to remove the merchandise.

Speaking personally, Clough said, “It’s part of history and the country, and we live with it.”

According to Harrell, the Confederate flag booth at the Addison County fair seemed especially glaring last year after the shooting of nine black churchgoers in South Carolina. The man charged with the killings, Dylann Roof, had posted photographs of himself online holding the Confederate flag and posing in front of pro-slavery heritage sites. In some photos he is also seen burning an American flag.

The killings reignited a debate over the Confederate flag, which had been displayed in front of the Capitol building in South Carolina since 1962. In response to the shootings last summer, South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley had the flag removed.

State fairs in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana also banned the sale of Confederate flag merchandise in the wake of the shootings.

After the decision in South Carolina, however, Harrell remembers seeing more Confederate flags in and around Middlebury. People were wearing bathing suits with the design. A flag was displayed prominently in front of a house on the edge of town along Route 7.

When Harrell got to the Addison County Fair with her three kids and saw the booth, it hit home, she said. Many of the flags had the slogan “Heritage not Hate” on them.

It was after another week of shootings in early July that the Middlebury chapter of the Unitarian Universalist Association began a series of meetings within the congregation about the Black Lives Matter movement and what the church could do to address the issue of institutional racism.

In one of those meetings Harrell learned there were black congregants who did not attend the Addison County fair in part because of the Confederate flag issue.

“Why at a family event where we’re trying to be welcoming to everybody, including the small minority of African-Americans and nonwhites who are part of our community, would you have this symbol associated with slavery for sale commercially?” asked the Rev. Barnaby Feder, of the Middlebury congregation.

The board’s decision was hardly a radical step, said Feder, but may lead to more substantive conversations.