(Editor’s note: This story is by Tommy Gardner, of the Stowe Reporter, in which it first appeared March 10, 2016.)

[L]ast year, the Rev. Benedict Kiely got so sick of hearing about the slaughter of Christians in Iraq at the hands of ISIS that he decided to use the terrorists’ own symbols against them.

Now, he’s learning what it’s like to live among the persecuted.

During their rise to power and throughout World War II, Nazis marked the homes of Jews with the Star of David, part of their effort to exterminate a whole race. ISIS does a similar thing in the regions where they operate, marking the home of Christians with the Arabic letter “N,” which denotes followers of Jesus of Nazareth.

“You get a sense of what it was like to be a Jew in 1938,” Kiely said. “ISIS is just a name for what’s been going on for a long time.”

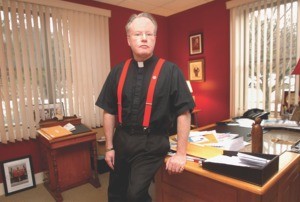

To help raise money for Christians under attack, Kiely, pastor of Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church in Stowe, launched the Nasarean Project, selling lapel pins, bracelets, magnets and zipper pulls, all black with the yellow Arabic letter “N.”

So far, the project has raised more than $150,000, with orders and donations coming in from all across the country, and from other countries, too.

“In our own little way, it’s had a worldwide impact,” Kiely said.

Proceeds from the Nasarean Project go to a group named Aid to the Church in Need, a Brooklyn nonprofit that strives to “help suffering and persecuted faithful worldwide,” according to its website. Kiely said the group provides housing, food and other support.

After Fox News did a segment on the project last year, Kiely and company sold out all their products — 25,000 items — in one day.

With help from some local businesses, such as the UPS Store, Kiely has been able to keep orders filled and overhead low.

Chelsea Collier, who volunteers her time, said people often donate money without even buying a pin or bracelet.

“Father Ben’s one of the best,” she said. The best what? “The best people.”

Esbert Cardenas Jr., owner of Image Outfitters, worked with his pastor — Cardenas is also a parishioner at Blessed Sacrament — to create the items.

“One day he came to me with tears in his eyes and said, ‘Esbert, we gotta do something,’” Cardenas said. “I did for him what I do. He ran with it, and God bless him.”

He ran with it, all right. All the way to the heart of the violence, all the way to a refugee camp in northern Iraq, where 120,000 fellow Christians eke out a daily existence, wondering if they’ll ever be able to return to their homeland, the cradle of Christianity.

Life in a bubble

When ISIS came to power in the summer of 2014, the group attacked and plundered cities all over northern Iraq, killing Christians and driving them from their cities, destroying priceless artifacts of the ancient Christian world.

About 120,000 people fled the cities of Mosul and Nineveh and found refuge in Erbil, a city in Iraqi Kurdistan that has become a bubble of security from ISIS as the terrorist group cuts a swath through the region.

Kiely was there earlier this winter and in May of last year. He describes it as a once-burgeoning metropolitan area that was suddenly placed on hold. Many of the Christian refugees are formally educated, middle-class citizens. The driver who transported Kiely and his entourage around the city had majored in political science.

“Erbil is an odd city. For instance, they have more unfinished skyscrapers than you’ve ever seen,” Kiely said. “They’ve gone from that to living in a container. With nothing. With nothing.”

Imagine something that’s a cross between a shipping container and one of those modular buildings where contractors on construction sites set up their offices: Those are the conditions in which the Christians and Yazidis who fled ISIS are living. The temperatures average 110 degrees in the summer.

Aid to the Church in Need helps provide some creature comforts in these container shelters, but they’re a far cry from many of the Christians’ former lives, as they squeeze into tight quarters with several family members. Not much privacy there.

“There’s hardly been any babies born in the past year,” Kiely said. “The camps are pretty forward-thinking, but you don’t want to live in a container.”

Kiely wants President Obama to call the Christians refugees and classify their “slaughter” as genocide, something Obama has not yet done.

Technically, since Erbil is in Iraq, the Iraqi Christians can’t be recognized internationally as refugees. The term is “internally displaced persons,” but Kiely knows better.

That term was also used to describe people from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina scattered the Big Easy all over the country. It’s still America, so they were internally displaced, but most people saw them as refugees of a sort.

Kiely understands why the Christians prefer to stay in Erbil, because ISIS is targeting refugee camps in other countries, targeting the Christians they find there, “slaughtering them barbarically.” The Yazidis, part of an ancient Kurdish religious sect that now numbers about 50,000, are at greater risk than the Christians. They all fear if they leave, that’s the end of their line.

‘Don’t have a clue’

The Jewish community has given the Nasarean project “a tremendous amount of support,” Kiely said. They know what it’s like to live for generations under persecution. He can’t say the same for much of America.

“American Christians just don’t have a clue as to what’s going on,” Kiely said. “So far, we haven’t had to face a test of how committed we are to our religion.”

The Christians in Erbil are descended from people who actually knew and walked with Christ. Kiely said that, during church services, he couldn’t understand a word being said, because everyone was speaking Aramaic, the same language that Jesus Christ himself spoke, and that almost no one still speaks. But he still felt the words, the rituals.

Imagine the pride of place a seventh-generation Vermonter feels. Now, imagine your line going back more than 2,000 years.

“They’ve been there, literally, since the beginning,” Kiely said.

Even worse, the popular backlash against refugees of all kinds, from Mexicans to Syrians, “has been disastrous” for people trying to advocate for them. “No government is speaking for the Christians, and they feel abandoned.”

Kiely said it’s up to Muslims to get Westerners to understand their religion, not the other way around, since ISIS is living a “literal seventh-century version of the Koran.” So, is Islam a religion of peace or one of war? A Jesuit priest told Kiely the answer is, “Yes. It’s a choice.”

“As a Christian, it’s not up to me to tell people how to understand Islam,” he said. “We’re looking at the complete eradication of Christianity in the Middle East. It’s a euthanization of the culture.”