[T]hink “The Rolling Stone Interview” is the easy-breezy stuff of celebrity? Not to Bernie Sanders. When the Vermont senator turned Democratic presidential candidate met up with the magazine last fall, he dispensed with formalities and dashed straight to the facts:

“I am the longest-serving independent in the history of the United States Congress.”

But read the resulting 7,500-word feature or any of the other national press profiles of Sanders and you won’t learn much about his quarter-century Washington career.

Time magazine’s Sept. 17 cover story “The Gospel of Bernie” notes “his winning campaign for mayor of Burlington in 1981 … launched Sanders on an upward trajectory that took him to Congress in 1991 and the Senate in 2007” — and nothing more on the subject.

Mother Jones, for its part, offers a similarly short passage in its nearly 5,000-word candidate biography, devoting just as much space to a description of how, as Sanders’ 1970s Burlington neighbor recalls, “He was living in the back of an old brick building, and when he couldn’t pay the (electric bill), he would take extension cords and run down to the basement and plug them into the landlord’s outlet.”

In one of the few national press pieces devoted to his congressional life, The New York Times wrote in August: “For all his newfound attention, Mr. Sanders is still regarded by his Senate colleagues as a peripheral figure whose surging presidential campaign is more of an endearing curio than a cause for reassessment. … He acknowledged that he has gotten little attention for what he has done. ‘This is the problem,’ he said. ‘I work in areas that nobody knows what I’m doing.’”

So what is Sanders doing? That depends on whom you talk to.

“Many senators respect Mr. Sanders’s consistency and fealty to his principles, his policy fluency and his ability to work with Republicans when he was chairman of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs to pass legislation that overhauled the veterans’ health care system,” the Times story continues.

“Others, however, consider such legislation a notable exception for a compromise-allergic ideologue who has over time managed to infuriate some moderate Democratic lawmakers resentful of his self-assigned role as the Senate’s liberal conscience,” the paper states. “Mr. Sanders is also not much of a favorite of Capitol Hill reporters who have grown used to his grumbling expressions of displeasure at the political nature of their questions.”

Such contradictions can leave many to wonder whether Sanders is strong-willed or stubborn. But according to the few campaign stories that chronicle his Washington accomplishments, he’s all of the above.

‘He’s unafraid to raise hell’

Shortly after Sanders announced his presidential bid last spring, Mother Jones became the first of several publications to summarize his entire political career — from his start with the alternative Liberty Union Party in 1971 to the surprises of his election as Burlington mayor in 1981 and Vermont’s sole congressman in 1990 and his ascent to the U.S. Senate in 2006 — in a few broad brushstrokes.

Rolling Stone, in a July feature titled “Weekend With Bernie,” elaborated a bit, but again by lumping Sanders’ congressional stint with all the ladder rungs that led to it.

“Sanders has always belied the easy caricaturing leftists are often subjected to, by taking a pragmatic approach to governing,” reporter Mark Binelli wrote. “In Burlington, he beefed up the city’s snow-removal operation, developed local parks and the waterfront, fixed potholes and negotiated lower cable bills for consumers (though he did also travel to Nicaragua to meet with socialist president Daniel Ortega, declaring Puerto Cabezas and Burlington ‘sister cities’). In the House, he became a procedural master, passing more roll-call amendments than any other representative in the decade beginning in 1995 and using his status as an independent to work with members of both parties. (Sanders’ facility for bipartisan outreach remains to this day: The ultraconservative climate-change-denying senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma recently described Sanders as his ‘best friend’ in the Senate.)”

Sanders’ campaign website, is one of the few places that notes he is the former chairman of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee and current ranking member on the Senate Budget Committee.

“In Congress,” it says, “Bernie has fought tirelessly for working families, focusing on the shrinking middle class and growing gap between the rich and everyone else.”

Most Vermonters who follow the news are familiar with Sanders’ accomplishments. But for voters outside the state, the candidate’s website offers a 26-point timeline that includes the following milestones:

July 1999: Sanders, protesting the prices charged by major pharmaceutical companies, becomes the first member of Congress to take older Americans to Canada to buy lower-cost prescription drugs.

March 2010: President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act becomes law with a Sanders provision expanding federally qualified community health centers and funneling $12.5 billion into offices that now serve more than 25 million Americans.

July 2010: Sanders, working with Republican U.S. Rep. Ron Paul, passes a measure as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill to audit the Federal Reserve to determine how the agency gave $16 trillion in near zero-interest loans to big banks and businesses after the country’s 2008 economic collapse.

December 2010: Sanders gives a filibuster-like speech lasting 8½ hours on the Senate floor in opposition to a deal to extend Bush-era tax breaks to wealthy Americans.

August 2014: Sanders, joined by Republican Sen. John McCain and Rep. Jeff Miller, wins passage of a bipartisan $16.5 billion veterans bill to, in part, help the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs hire more health professionals to meet growing demand.

‘It can be tough to strike a balance’

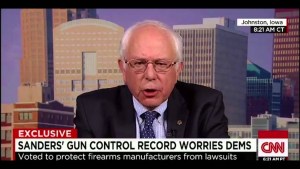

But even the most exhaustive national press profiles are scattershot in reporting that record. Instead, they target something else: his view and votes on guns.

“His legislative history is actually far to the right of Hillary Clinton’s when it comes to guns,” Rolling Stone opines in its “Weekend With Bernie” story. “Sanders actually owes the start of his congressional career, in part, to the National Rifle Association.”

The New Yorker magazine outlined the history in an October profile titled “The Populist Prophet.”

“When Sanders first ran for the House of Representatives, in 1988, he lost to a Republican named Peter Smith, the scion of a banking family,” staff writer Margaret Talbot began. “During Smith’s first term, he co-sponsored an assault-rifle ban. In 1990, Sanders ran again, and the N.R.A. went after Smith, sending letters to its Vermont members describing Sanders as the lesser of two evils, since he wasn’t publicly supporting the ban. Sanders won. This is the origin of the critique that Sanders has weak gun-control credentials for a progressive.”

As National Public Radio’s “Morning Edition” broadcast would point out in a story headlined “Bernie Sanders Walks A Fine Line On Gun Control”: “For left-leaning senators from largely rural, pro-gun states — like Vermont — it can be tough to strike a balance talking about guns.”

Sanders knows. Just before this month’s NBC News-YouTube Democratic debate in South Carolina, he announced he would support legislation to amend a 2005 law on gunmakers’ liability that he originally voted for. But that hasn’t stopped his main rival, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, from exploiting the issue as metropolis after metropolis grapples with mass shooting after mass shooting.

“It’s time to pick a side,” Clinton says in a television commercial now airing nationally. “Either we stand with the gun lobby, or we join the president and stand up to them. I’m with him.”

The New Yorker adds: “In national office, Sanders has not been a vocal proponent of strict gun control. In 1993, he voted against the Brady Bill, objecting to its imposition of a five-day waiting period to buy a handgun. And in 2009 he voted to allow guns in national parks and on Amtrak trains. Over the years, he has also voted for some restrictions, including a semi-automatic-assault-weapons ban and instant criminal-background checks. The N.R.A. has given him grades ranging from C- to F. (It’s a tough grader.) But he has never been out front on the issue, partly because it doesn’t seem to engage him deeply, and partly because he wants to retain the loyalty of voters in northeast Vermont, where hunting is popular.”

The magazine went on to quote Sanders: “I think I’m in a good position to try to bridge the gap between urban America — where guns mean one thing, where guns mean guns in the hands of kids who are shooting each other or shooting at police officers — and rural America, where significant majorities of people are gun owners, and ninety-nine per cent of them are lawful.”

Such comments have yet to assuage Clinton.

“If you’re going to go around saying you’ll stand up to special interests,” she was recently quoted by Time magazine, “stand up to the most powerful special interest — stand up to that gun lobby.”

‘Reimagined the role of the legislator’

Sanders would rather talk about the economy. But national news outlets have reported little about his attention to it in Congress.

A front-page New York Times story Aug. 15 — “Sanders Fights Portrait of Him on the Fringes,” read the headline — is one of the few to tackle the issue. In it, reporter Jason Horowitz tracked the senator not on the campaign trail but all around the capital.

“Mr. Sanders’s disdain for the things he views as unimportant is matched by his single-minded focus on the things he says are of real consequence, like the future of Social Security,” Horowitz wrote.

“At the Democratic caucus lunches, at which he is a fixture, ‘all he ever talks about is Social Security,’ one congressional aide said. ‘He doesn’t even try to relate it to the topic at hand.’

“That focus was on display a few weeks ago when, on an especially slow day in the Senate with only a minor vote on the schedule, caucus members piled onto buses for a White House meeting with President Obama. Looking around the room, Mr. Obama was surprised to see Mr. Sanders.

“‘Bernie?’ he said. ‘Shouldn’t you be out in New Hampshire?’ There was a chuckle, and then the president asked Mr. Sanders what was on his mind.

“‘Social Security,’ Mr. Sanders said.”

Concern about cuts to the federal assistance program spurred Sanders’ opposition to the president’s 2011 budget efforts — which, in turn, led Senate Democratic leaders to limit his role in negotiations last fall, according to the Times, even though Sanders is the ranking member on the Budget Committee.

Asked for his congressional accomplishments, Sanders cites pushing for billions of dollars of investment in energy-efficient technologies in the stimulus bill and tripling funding for the National Health Service Corps, which forgives debts for medical students who commit to working in underserved fields and communities.

“The way he sees it,” the Times reported, “his career has not been that of a gadfly on the margins of Congress, but rather that of a moral force pulling the mainstream toward his positions.”

The candidate says the same thing about his early opposition to the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act denying federal benefits to same-sex couples (“President Clinton signed it, everyone was for it”), the 1999 deregulation of Wall Street (“Check the record! Do it. Go to YouTube, look up ‘Bernie Sanders, Alan Greenspan’”), and the 1991 Persian Gulf War, 1993 North American Free Trade Agreement, 2001 USA Patriot Act, 2003 Iraq invasion and 2015 Keystone pipeline plan.

Sanders also can point to perhaps the most extensive review of his congressional career: The Nation correspondent John Nichols’ new afterword to the candidate’s 1997 autobiography “Outsider in the House” — which Verso Books, the self-described “largest independent, radical publishing house in the English-speaking world,” recently revised and reprinted under the name “Outsider in the White House.”

Nichols, detailing Sanders’ quarter-century political record year by year in his 42-page afterword, notes how the U.S. Capitol’s longest-serving independent continues to defy convention.

“The best members of Congress, of all ideologies and on both sides of the aisle in the House and Senate, respond to crises, challenges, and opportunities outside Washington by launching inquiries, holding hearings and proposing legislation,” the journalist writes. “But Sanders reimagined the role of the legislator, working all the angles on Capitol Hill and then hitting the road to urge citizens at home in Vermont and across the country to pressure Congress to address climate change, to save the Postal Service, to recognize and respond to the damage done by trade policies that led to dislocation and unemployment — especially for African Americans, Latinos, and the young.”

The question now: Can Sanders follow the same path to the White House?

(Coming in part five: The national press corps, befuddled for months about how to cover the profile-phobic Bernie Sanders, now faces a bigger challenge: predicting the rest of the story.)