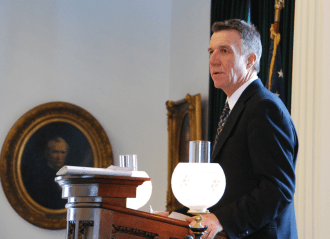

[L]t. Gov. Phil Scott was called on to cast a rare tie-breaking vote in the Vermont Senate on Thursday on a toxic chemical provision.

[L]t. Gov. Phil Scott was called on to cast a rare tie-breaking vote in the Vermont Senate on Thursday on a toxic chemical provision.

The amendment would have strengthened regulations on manufacturers who sell children’s products containing toxic chemicals. The changes were tucked into an omnibus health care bill, S.139, which includes tougher regulations for pharmacy benefits managers and requires hospitals to notify patients when they are placed on observation status, which can determine whether services can be covered by Medicare.

Scott broke the 15-15 deadlock and voted against the toxic chemical provision. He said he was reluctant to pass new changes when the law has not been fully implemented.

“It’s been less than a year and I don’t think that’s enough time to really find out the pitfalls or the benefits of the legislation,” Scott said. “I think the Legislature has a history of reacting fairly quickly. If there is an issue that comes up, that will be dealt with.”

The floor debate focused on proposed changes to Act 188, which put in place new chemical safety regulations for children’s products. Gov. Peter Shumlin signed the law in June.

Proponents of the amendment wanted to simplify the process for regulating toxic chemicals. They also feared that proposed federal legislation now in Congress would preempt future changes to the law.

The amendment would have allowed the state health commissioner to issue regulations without prior consent from a special advisory group that would include representatives from industry and advocacy groups. Another change would have reduced the amount of scientific evidence needed to allow the commissioner to regulate certain chemicals.

Industry groups and public health advocates lobbied lawmakers on their side of the issue before the vote. Public health advocates said the changes would allow the law to be implemented as lawmakers intended. Industry representatives said the changes would undermine the credibility of the regulatory process.

Sen. Ginny Lyons, D-Chittenden, who introduced the legislation last session, backed the proposed amendment for more “effective and understandable” regulations. She said the Senate Health and Welfare Committee did not have a chance to react after the House eliminated the tougher regulations late in the session last year.

“It doesn’t mean we won’t come back again. Someone suggested I put in a bill and I think I will,” Lyons said.

Bill Driscoll, vice president of Associated Industries of Vermont, said the changes would have allowed the Department of Health to issue “arbitrary or subjective” regulations.

But public health advocates say the current legislation sets a high bar — and one that might invite legal challenges — if the commissioner regulates certain chemicals.

“It just really means that it could actually work,” said Paul Burns, executive director of the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, of the proposed amendment. “The commissioner could actually move forward, not ‘arbitrarily,’ but after a rigorous process.”

Advocates are concerned that it could be possible to stack the working group with pro-industry representatives. The advisory group must first make recommendations to the health commissioner before regulations can be issued.

The working group includes 11 members — the commissioner of health; the commissioner of environmental conservation; a state toxicologist; a public health advocate; an expert in children’s health or pregnancy; a representative from a business that uses toxic chemicals; a toy industry representative; a scientist; and three members appointed by the governor.

The working group has not been set up, according to the Health Department.