Editor’s note: This article is by Matt Hongoltz-Hetling, of the Valley News, in which it was first published Dec. 9, 2014 .

“Meet Sam.”

A man’s friendly voice is clear above the gentle piano music playing in the background of the video, and as he says the words, a hand reaches into the blank white frame and draws a little crescent-shaped squiggle with a black pen.

“He recently returned from serving in Iraq,” the voice says. In the video the hand draws another, larger line that connects to the squiggle, and then another. In just four seconds, the hand, moving in fast-motion, has drawn Sam’s upper half; that first mysterious squiggle has been transformed into Sam’s right ear.

“For many people, being in a crowded place like a baseball stadium or a busy grocery store feels comfortable. But not for Sam.”

As the voice keeps talking, the hand rapidly sketches a menu in Sam’s hand, a pretty, pony-tailed woman sitting across from him and a table covered in a white tablecloth with a candle on it.

“What should be a nice night out, taking his wife Tara to a restaurant, isn’t fun for him anymore,” the voice says. “He can only handle it if he sits with his back to the wall, where he has a good view of the exits, and even then, he’s too on edge to really enjoy it.”

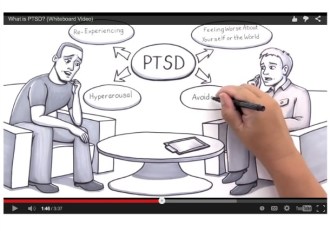

The scene comes early in a video that, in just 220 seconds, introduces viewers to the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder, some common causes and symptoms, and the idea that people who recognize those symptoms in themselves or loved ones can find help.

The video was commissioned by the National Center for PTSD of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, located in Hartford, in the hopes that animations like this — often called whiteboard animation, or video scribing — will find resonance within a public that is increasingly focused on social media channels like Facebook and Twitter.

“It’s a new form of media for us,” said Rebecca Matteo, the National Center’s Web content manager.

When Matteo and other decision makers at the VA plunked down nearly $100,000 to a company to create the video, and five others like it, they weren’t acting alone.

Thousands of whiteboard animation videos, some of which garner millions of views, can easily be found on YouTube promoting a wide range of products and ideas, everything from an explanation of the tangled Justice League storyline in the DC Comics universe, to NBC’s coverage of the 2012 presidential debate.

One, put together for the grocery store chain Trader Joes, features audio of phone calls from customers raving about their shopping experience, while another, from online retailing giant Amazon, walks potential sellers through the process of setting up an Amazon shop.

In all of the videos, the unique element is that pencil-holding hand, which commands the viewer’s attention as it buzzes through drawing after drawing, making sense of the accompanying spoken words.

The sophistication of the marketing technique, and the depth to which it has permeated modern culture, are all the more amazing given that it didn’t even exist a decade ago.

A New Industry

As with most art forms, it is difficult to pin down the origins of whiteboard animation.

The idea of including the artist’s hand inside a cartoon dates back to at least the 1940s, when, in one famous Bugs Bunny cartoon segment, the rabbit was plagued by a giant hand that uses pencils and paintbrushes to change his body and his surroundings.

Some whiteboard animation companies credit the popularization of the idea to UPS, which in 2007 launched a series of commercials in which a fully visible artist sketched ideas on a whiteboard with a magic marker. The commercials aired on television, but they were also an Internet sensation, racking up hundreds of thousands of views and spawning hundreds of parodies lampooning the style.

Within a few years, whiteboard animations in their modern form were cropping up all over on the Internet.

With a recession in full swing, 2010 was not a good year to be a fledgling company specializing in foreign currency and hedge funds, realized Curtis Pace and Jace Vernon, lifelong friends from Utah who went into business together at the age of 30.

In an effort to boost business, the two tried to commission a whiteboard animation, which seemed like a fresh, innovative way to stand out from the competition.

But they could only find a single company that specialized in producing high quality whiteboard animations, an England-based firm that charged upwards of $30,000 per video — far out of their price range.

Pace said that one day, Vernon turned to him with an idea.

“‘You can draw,’” Vernon said to Pace. “‘Let’s do this.’”

They put a video about the technique up on YouTube one day at 8 a.m. By 3 p.m., they had their first client, and Pace said the phone hasn’t stopped ringing since.

Now, just four years later, the pair’s company, Ydraw, has 15 full-time employees and a larger stable of freelance voice actors and artists, who have 120 videos in production at any given time.

In all, Pace estimated, they’ve produced nearly 1,000 animations, including the ones used in the campaigns by Amazon, and the VA. The average client pays about $8,000 for a 90-second video, about twice what Ydraw charged when it first opened its doors, Pace said.

The flood of interest is opening up new opportunities for cartoonists like those at the Center for Cartoon Studies, also in Hartford, where Michelle Ollie, president and co-founder, said she has seen a drastic acceleration in calls for the technique.

“It hit the pop culture a few years ago,” she said. “People see it as a successful way to communicate.”

The center has produced videos for nonprofits like State of the Re: Union, which celebrates community values, and Positive Tracks, which helps young people raise funds for charitable causes.

Right now, Ollie said, the center is working with the engineering college at Dartmouth College to create a whiteboard animation explaining a new offering, the Massive Online Open Course.

Ollie said the technique capitalizes on a truth that the cartooning community has been espousing for years: words and pictures together pack a powerful one-two punch.

The rapid-fire hand adds in a compelling “behind the scenes” element that invites your brain to puzzle out the emerging graphic and gives you an unusual glimpse of the creative process.

“It has that great sort of magical illusion,” Ollie said. “It feels more original. It has that illusion of spontaneity.”

Pace said that only about one in four viewers watch the average YouTube video through its entire duration, but that three in four viewers watch Ydraw’s whiteboard animations all the way through.

“It goes back to our childhood. Our grandparents loved watching cartoons, and we loved watching cartoons,” he said. “Now you have the ability to watch someone draw this stuff out. It’s so intriguing.”

Helping Veterans

While whiteboard animations have taken off as an industry, the success of any particular video is not guaranteed.

At the VA’s PTSD Center in Hartford, Matteo is keeping an anxious eye on the number of views for the five videos she released on the agency’s website this week.

Matteo said that while there is increasing public awareness of PTSD, people often fail to make the connection between a list of symptoms and what’s going on in their own lives.

“When you go through a trauma, the last thing you want to think about is, ‘Do I have a clinical diagnosis?’” she said. “We’re just trying to get through the day.”

The first video, which told the story about Sam and his wife, Tara, successfully treating his PTSD, was released on June 27, PTSD Awareness Day, and has been viewed more than 82,000 times.

Juliette Mott, a psychologist and education specialist at the VA, said she sees even more encouraging signs in the online comments and other forms of feedback the team has received.

“Users are watching the video and they’re saying, ‘That sounds like me. That sounds like my husband,’” she said. “That was our goal. We wanted people to see this and give them a route to see their doctor and seek help.”

If the other five videos also prove to be successful, she said, the technique will have made an even more significant difference in the lives of thousands.

“For many, there are a lot of unknowns about PTSD,” she said. “This removes a lot of the mystery.”