In This State is a syndicated weekly column about Vermont’s innovators, people, ideas and places. Details are at maplecornermedia. Candace Page is a Burlington freelance writer.

In the late 1830s, a slave named Simon escaped his Maryland master and fled to southwestern Pennsylvania. His skill with horses and reputation as an excellent fieldhand meant he would not lack work.

Still, he could not sleep easily. Slave-holding Maryland was too close by.

Vermont abolitionist Oliver Johnson met Simon in January 1837 as Johnson canvassed Pennsylvania for the American Anti-Slavery Society. He offered to help Simon travel the Underground Railroad to Vermont, to a job with the abolitionist Robinson family of Ferrisburgh.

Simon “intended going to Canada in the spring, but says he would prefer to stay in the U.S. if he could be safe,” Johnson wrote to Rowland Thomas Robinson. “I have no doubt he will be perfectly safe with you.”

At Rokeby, the Robinson family’s home and farm, Simon would join other fugitive slaves, free and safe for as long as they chose to stay.

This week, more than 175 years after Simon’s escape, the Rokeby Museum on U.S. 7 will open a $1.3-million exhibit space dedicated to his story and that of other African-Americans who escaped bondage.

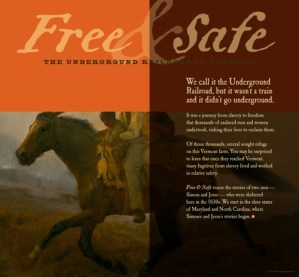

The permanent exhibit, “Free and Safe,” for the first time brings to broad public view a reliable picture of Vermont’s role in the Underground Railroad, that network of abolitionists who helped escaped slaves travel north.

“Free and Safe” also represents a major expansion, and a major financial risk, for the small house museum that, until now, lacked even potable water and public bathrooms. Visitors have been limited to guided tours of the farm outbuildings and a sprawling 18th-century farmhouse, crammed with furniture and artifacts left behind by four generations of Robinsons.

“This is the most important thing that happened here,” museum director Jane Williamson said recently, as she showed off the exhibit. “This is a story we had to tell.”

“Free and Safe” strips away local Vermont legends that have turned attic rooms and chimney corners in dozens of communities into places where runaway slaves were hidden.

“Stories about the Underground Railroad in Vermont are vastly exaggerated,” says University of Vermont historian Kevin Thornton. “There was no reason to hide a slave in Vermont. This idea that there were hidey-holes everywhere is just nonsense. Rokeby is one of the few true-blue sites.”

In a survey for the state in 1995, the Norwich University historian, Raymond Zirblis, examined the claims that linked 174 Vermont people or sites to the Underground Railroad. He could find sure documentation for only 25 of them and persuasive but inconclusive evidence for another 32.

Rokeby is a “true-blue site” because the Robinson family was “a bunch of crazy pack rats,” Williamson says.

From their arrival from Rhode Island in 1793 to the death of the last Robinson in 1961, the family “saved everything.” That includes the voluminous correspondence Rowland Thomas and Rachel Robinson, Quakers who were perhaps Vermont’s leading radical abolitionists, carried on with peers across the North.

Among the thousands of documents at Rokeby, researchers found Oliver Johnson’s letter seeking help for Simon.

A second important set of letters tells the story of Jesse, a black farmworker at Rokeby who had escaped his owner in North Carolina. Jesse had saved $150 from his Rokeby wages and hoped to buy his freedom. This was “the most anxious wish of his heart,” Robinson wrote to Jesse’s former master.

The North Carolinian’s reply was revealing. “At this time (Jesse) is entirely out of my reach,” he acknowledged – while insisting on a price of $300.

“Out of my reach,” explains why Jesse, Simon and other escaped slaves did not need to hide in caves or cupboards in Vermont.

Although Vermont was the first state to outlaw slavery, this state was not considered a haven because sturdy, freedom-loving Vermonters were all ready to defy any slave owner seeking to recover his “property.”

“Oh, pul-leeeze,” Williamson scoffed at that self-congratulatory version of history. Thornton, the UVM historian, notes that in the 1830s abolitionists were often seen as “interfering moralists.” In 1835, a mob stormed a Montpelier church where an abolitionist was speaking.

No, Vermont was safe for runaway slaves for reasons of geography not policy.

“Vermont was too far away,” Williamson said. “Trying to track down a slave, even from Maryland – that’s very, very expensive and takes forever. And even if you got here, the slave could easily go over the border to Canada.”

Instead, a picture emerges in “Free and Safe” of Vermont as a place where former slaves could live openly, finding the right combination of farm employment and relative security from recapture.

At Rokeby, former slaves worked on the prosperous family’s 850-acre merino sheep farm. A number of African-American families lived independently in Addison County. At a school on the Robinson property, black and white children attended class together.

Despite this tranquil picture, the story told in the Rokeby exhibit carries its own drama and human pain.

Fleeing through the South, leaving friends and family behind, uncertain of their safety even in the North, African-Americans lived lives of anxiety and deep sadness.

“Just because Jesse was safe at Rokeby doesn’t mean he felt safe,” Williamson said.

Williamson’s fly-away gray hair and restless hands were in constant motion as she talked with passion about Rokeby and its new visitor center/museum.

She first came to Rokeby as a volunteer, having fallen in love with the crowded farmhouse and its story on a tour in 1989. She became executive director in 1995.

Expanding Rokeby’s mission to include the Underground Railroad story faced such daunting obstacles that “‘challenge’ doesn’t seem like a big enough word,” Williamson said.

First came the conceptual difficulty of telling the stories of Simon and Jesse dramatically enough to engage visitors – while staying faithful to a historical record remarkable for its gaping holes.

Rokeby’s documents do not even provide the last names of the two slaves. Their full stories are unknown. Their voices are not heard in the written record.

The sophisticated exhibit addresses those problems by guiding visitors through a series of rooms that embed Simon, Jesse and Rokeby in the broader story of slavery, escape and the Underground Railroad.

Visitors can press buttons to listen to black voices reading the words of former slaves who wrote of their experiences. A play in four voices by Vermont poet David Budbill allows Jesse to speak his mind.

Financing the expansion was equally daunting. A museum with a $67,000 annual budget faced raising up to $1.3 million.

Two elements proved key: a lead gift of $500,000 from Shelburne philanthropist Lois McClure, and Rokeby’s status as a National Historic Landmark, one of the nation’s best-documented Underground Railroad sites. The museum won $200,000 grants from three federal programs; individual donors pledged $200,000.

Seth Bongartz, executive director of Hildene, the home of Abraham Lincoln’s descendants in Manchester, describes Rokeby’s fundraising success as “very, very impressive.”

Historic-home museums like Rokeby and Hildene, “are not going to make it if they are just beautiful do-not-touch places,” he said.

“Rokeby is a unique place with a unique story,” he said. “They have a responsibility to tell that story, but also an opportunity. People want to be engaged intellectually and emotionally with a story that is about the future as well as the past.”

Williamson said she hopes “Free and Safe” will meet that test.

“Race continues to be a significant problem,” she said. “We hope the exhibit will contribute to the conversation – showing the importance of taking a stand and pointing the way to racial tolerance.”

As painters and electricians put the final touches on “Free and Safe,” Williamson almost bounced with excitement and nervousness.

“We were on the decline. We had to pull out the stops and try to tell this story,” she said. “If we close in five years, at least we tried.”