Editor’s note: This article first appeared in The Commons.

The Entergy v. Vermont trial in U.S. District Court concluded Wednesday in Brattleboro, and Judge J. Garvan Murtha has plenty to consider.

Did Vermont, as Entergy contends, improperly stray into the realm of federal regulation in seeking to shut down Vermont Yankee? Or is Entergy, as the state contends, going back on previous legal agreements that allowed Vermont to have a say in the plant’s future?

Murtha is expected to take up to two months to issue a decision in this lawsuit.

In her closing argument, Kathleen Sullivan, the lead attorney for Entergy Nuclear, the owners of the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant in Vernon, continued to press the theme that the state has overstepped its bounds regarding the regulation of nuclear power.

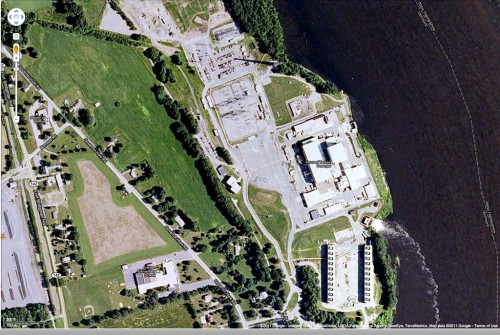

Entergy has sued the state over its denial of a Certificate of Public Good to operate Vermont Yankee past the expiration of its current license in March 2012. Earlier this year, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a 20-year license extension to Entergy.

Entergy attorneys have told the court that they hope Judge J. Garvan Murtha will overturn three Vermont statutes: Act 74, Act 160 and Act 189.

Sullivan has been trying to show that nuclear safety concerns — which are the sole purview of the NRC — are what drove the Vermont Senate in 2010 to defeat a bill that would have allowed the Public Service Board to issue a CPG for Vermont Yankee.

Sullivan pushed Entergy’s closing statements over six hours, plus approximately 30 minutes of rebuttal, in response to the state’s closing arguments.

Sullivan contends that any other reasons that the state has given for closing the plant in 2012, like economic concerns, are merely pretexts for discussing nuclear safety issues, and she played several recordings of legislative sessions to bolster that point.

Rather than shut the plant down, if the state didn’t like us, then “don’t do business with us,” she said.

If you [Vermont] don’t like the deal the company offered in its purchase power agreement [PPA], is the remedy to shut the plant down?”

– Kathleen Sullivan

Entergy lead attorney

Citing the 1983 Pacific Gas & Electric v. California Supreme Court case, Sullivan maintained that the court needed to decide the case by considering legislative intent by way of Vermont’s legislative history.

Sullivan maintained that the state had no evidence supporting that the purposes stated in Act 74, Act 160 and Act 189 matched what the legislators were truly thinking.

Sullivan argued that the state gave “hypothetical” examples, and didn’t show what legislators “actually” did.

“A theoretical legislature might hypothetically try to promote” other, non-nuclear safety energy goals, she said.

The state offered no evidence of what “the actual Legislature had in mind,” Sullivan said in reference to Act 74.

Act 74, enacted in 2005, regulates the dry cask storage of spent nuclear fuel at VY and requires Entergy to seek permission from the state to store additional fuel past 2012.

Sullivan also argued that Vermont’s decision to shut down Vermont Yankee, through its 2010 Senate vote, violated the dormant commerce clause. The decision, she said, “discriminated” against the other New England states because it didn’t allow them to purchase power from Vermont Yankee after 2012.

“If you [Vermont] don’t like the deal the company offered in its purchase power agreement [PPA], is the remedy to shut the plant down?” she asked the court.

In her rebuttal, Sullivan painted a picture of a power plant forced to acquiesce to a state’s pre-empted, nuclear safety-related regulations “against its will.”

Sullivan said the state broke its commitment to Entergy “in a fundamental way” with Acts 74 and 160.

“This wasn’t a negotiation, it was a coercion,” she said of Entergy’s agreements to Vermont’s regulations.

In two hours of closing arguments, the Vermont attorney general’s counsel, Bridget Asay, asserted the state steered clear of the federal pre-emption laws regarding nuclear safety.

Assay said the state’s statutes that regulated Vermont Yankee fell within the “permissible” territory of concerns like economics and the state’s long-term energy goals.

Asay also cited the PG&E case, saying the Supreme Court focused on the text and stated purpose of California’s statutes.

Entergy’s route of using legislative history to determine a statute’s final intent “contradicted” the Supreme Court’s precedent, she said.

According to Asay, the Supreme Court chose to not consider legislative history because how could a court pinpoint the motivation of every lawmaker voting on a bill?

Statutes, she said, were the product of a process of deliberation.

Instead, Entergy’s approach of studying legislative history asked the court to find that Vermont’s 180-member citizen Legislature had conspired over multiple sessions to lie within its statutes.

Asay said by choosing to sue the state, Entergy had broken its commitments and signed contracts. She asked the court not to allow the company to “walk away” from its agreements.

Asay also presented the court with documents and audio clips from Entergy management pointing out where the company acknowledged the state’s authority to regulate the plant.

The company engaged with Vermont’s legislative process and made commitments, she said, as long as everything worked to Entergy’s benefit.

Speaking outside the courtroom Wednesday, Vermont Attorney General William Sorrell said that nuclear safety was not the sole pretext for the state’s decision not to issue Vermont Yankee a certificate to operate the plant through 2032.

He cited the loss of trust in Entergy after the revelations of leaks of tritium-laced water from underground pipes that Entergy officials said did not exist at Vermont Yankee. He also cited the attempt by Entergy to spin off Vermont Yankee and five other plants into a new corporation, and the lack of a favorable power purchase agreement.

He said the burden is on Entergy to prove that Vermont was only focusing on safety in its policy making.