Editor’s note: This article, by Daniel Richardson, was first published on SCOV Law Blog.

U.S. Bank N. A. v. Kimball, 2011 VT 81

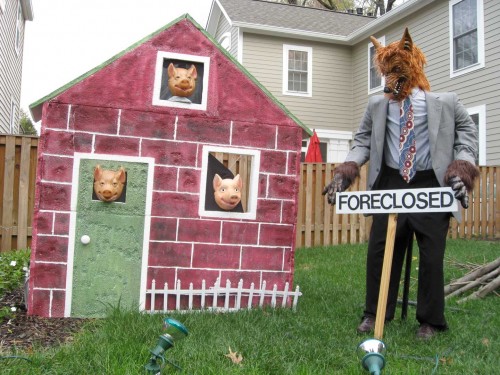

There are two competing narratives dominating the foreclosure epidemic of the past three years. For banks and mortgage security holders, the story is one of lost revenue on an unprecedented scale.

For homeowners, it is a bureaucratic nightmare of dark alleys and dead ends where it is difficult to figure out whom you are working with, let alone to negotiate with anyone holding real power. It is a situation where every day the loss of your home, your savings and your equity looms large.

Here is the dirty secret of the mortgage crisis. Banks and mortgage companies are fundamentally ill-equipped to handle the massive number of foreclosures that have arisen.

In a nutshell, banks and mortgage companies originate mortgage deeds by lending money to individuals to buy their home. Those mortgages are then sold on secondary and tertiary markets to various investor groups that hold them like stocks or other securities. Capital flows and mortgages are simply paper markers that generate income and represent a set of investment potentials. It is a hands-off game where the emphasis is on trading, investing and larger market research. Mortgage servicing companies like MERS or GMAC are hired to do the day-to-day maintenance, but they are often kept apart from the investor groups who, like absentee landlords, buy the loans and then walk away.

If you have a mortgage, chances are you have never spoken to the owner of your mortgage deed. If you have spoken to anyone, it was probably to an agent of the servicing company. This is someone who has about the same authority over your mortgage as a gardener at a Bel Air mansion has over redecorating the west wing.

This formula works well so long as the mortgage is paid and money flows through the joints of the system. Shut that money off and begin default, and issues quickly arise. The well-oiled investment machine starts to behave like a high school dropout at exam time.

Bank of America, for example, went from one of the country’s premier financial institutions to the nation’s largest clearinghouse for foreclosure litigation. All of the analysts, bankers and managers that safeguard the bank’s assets are now the vanguard of a litigation team that must go to every town, big and small, in the United States to convince courts to kick local residents out of their homes.

This brings us to today’s case. A homeowner was sued by a U.S. bank for defaulting on her mortgage. In the original complaint, the bank included an unsigned copy of the mortgage but not a copy of the note. The homeowner sought to dismiss the claim for lack of evidence that the bank owned the note. In support, the homeowner included documents she had received from a mortgage servicing company indicating that someone else owned her mortgage. The bank amended its documents by producing a copy of the note that was signed but undated. It also submitted an affidavit from a cog at the mortgage servicing company who testified that he believed the U.S. bank to be the owners. The trial court, leery and suspicious of so many questionable documents from the bank, granted the motion to dismiss and did so with prejudice. The homeowner asked for attorney’s fees, but she was denied.

On appeal, the bank’s arguments give the Supreme Court of Vermont a nice opportunity to expound on mortgages 101. When you borrow money from a bank or anyone else, the key document is the promissory note. This note is the actual promise to pay the lender back. The mortgage is just a security document that says if the note is not paid, then lender can look to the property and gives lender first place in the line to recover.

The big first question in any foreclosure is whether the bank can show that at the time of filing it owns the note. Notes like any other paper instrument must be transferred in particular ways. The Supremes have a nice primer on the function difference between transferring a note that says “pay to the order of” and one that says “pay to the bearer.” Future bar examinees take note!

Regardless of what the note said, the U.S. bank was not able to show that it had proper ownership of it at the time the complaint was filed. At best, the U.S. bank could show that it acquired and possibly perfected its ownership of the note some time after the litigation began. In fact, the circumstantial evidence is strong that the bank did not, at the time of filing, properly own the note and tried to cover up this fact by omitting dates and introducing affidavits based on the conclusions of the banks’ agents rather than personal experience. With such evidence, the Vermont Supreme Court has no problem upholding the dismissal as the bank failed to meet the basic criteria for filing a foreclosure.

Here is the rub for the homeowner. This victory, sweet as it might be, is destined to be short lived. The trial court dismissed the case with prejudice, which normally means that the plaintiff cannot re-file. The Supreme Court, however, rules that you cannot dismiss a foreclosure with prejudice, particularly when the basis is a lack of standing, which can be cured in the future. The Supremes are quite explicit here. The bank can simply re-file its complaint to revive its claims. So the homeowner’s victory only buys her a few more months unless she and the bank can settle.

To the uninitiated, this decision can seem cruel and unfair, but it is a reasonable extension of the logic behind foreclosures. In most foreclosure cases, the issues are not complex. A bank owns the note, and defendant has not paid. The note is secured to property, and bank is usually entitled to take possession to sell the property to recover amounts owed. In this respect, foreclosure is just a formal court process that guides the parties through enforcement of their agreement. In this case, there is no dispute that the homeowner took out a loan and received the benefit of that loan. There is also no dispute that she has not made her payments as agreed to by the terms of the note. The only question is what process the bank is entitled to follow to recover its investment. The current suit is flawed, but they can try again because the fundamental relationship has not been disproved or substantially altered. That was the deal at the beginning of the loan, and nothing has changed.

All is not lost for the homeowner — she gains a significant victory from the Supremes in the form of attorney’s fees. The Vermont Supreme Court rules that the facts support such an award and remands the case to the trial court for the homeowner to present evidence of attorney’s fees. This is a big win because the Supreme Court’s ruling highlights its shared belief with the trial court that the bank has acted very badly in this litigation. It is a small victory, however, since the homeowner’s counsel was from Legal Aid who likely worked for little or no actual cost to the homeowner.

At the end, you can see both sides pulling out their hair. The bank’s attorney has the unenviable job of explaining to some executive why they will have to start from scratch in this foreclosure case (Answer: because the bank failed to get its documents in line before starting the litigation). The homeowner, meanwhile, can only savor her bittersweet victory with the knowledge that another round of foreclosures are coming down the pike — and the bankers know her address.