As the son of a dentist, David Remnick spent plenty of time in his youth flipping through the pages of the New Yorker in his father’s waiting room.

“Among the most visually recognizable artists of my growing up was Ed Koren,” Remnick said. “He was on the cover. He was in the magazine, constantly. He was an artist that a child could understand and yet came from the most adult sophistication.”

When Remnick landed at the New Yorker in 1992 — three decades after Koren sold his first cartoon to the magazine — he “made it (his) business to kind of bump into this guy” who’d loomed so large in his mind since childhood.

“And he was as advertised,” said Remnick, who has served as editor of the New Yorker since 1998. “He was sophisticated, but he was also immensely generous and sweet and kind and all those things. There wasn’t an ungenuine bone in his body.”

Koren died last Friday at his home in Brookfield. He was 87 years old.

In his final years, as he reckoned with lung cancer and associated health setbacks, Koren could no longer keep the pace he’d set as a surprisingly spritely octogenarian — skiing and cycling throughout Vermont, dancing the night away at weddings, jetting off to Paris and, famously, serving on the Brookfield Volunteer Fire Department.

But according to friends and colleagues, Koren still managed to do much of what he loved most — working away in his studio, swapping stories with old pals and spending time with his beloved wife, Curtis.

His final cartoon — depicting Moses holding up the Ten Commandments, with the caption, “Time for an update!” — appeared in the New Yorker the very week he died.

“He went out with his boots on,” said the cartoonist and graphic novelist Alison Bechdel. “It’s incredible.”

James Sturm, a cofounder of the White River Junction-based Center for Cartoon Studies, visited Koren regularly in recent months and recalled the artist trying to offload books from his collection. “You’d pull a few and he’d say, ‘Not that one. I might still read that one.’”

Koren’s death may not have come as a surprise, Sturm said, but it was nevertheless “heart-wrenching.”

“He was so open about the process of dying, and he brought laughter to that process, and he never shied away from what was going on,” Sturm said. “I just found that very instructive. This is how I want to face the inevitable, as well. His example was a gift — not just as a cartoonist, but as a person moving through this world.”

Writer and journalist Jonathan Mingle visited Koren last fall and took a tour of his studio, where the artist walked him through his method. “You could tell he hadn’t lost any of the glint and gleam in his eye for any part of that process,” Mingle said.

Nearly half a century younger than Koren, Mingle was part of the multigenerational network of friends Ed and Curtis cultivated and socialized with over salon-like dinners in Brookfield. And though they worked in different fields, Mingle said, he recently realized that Koren had been “a stealth mentor.”

“There are certain people in your life who, over time, you realize that being around them is so nourishing,” Mingle said. “I just came away from every dinner or conversation or encounter with Ed feeling buoyed in some way.”

Like Remnick, many of Koren’s friends knew of Ed long before they knew him — and that could be intimidating, at least at first.

“I was pretty, you know, star-struck by meeting him,” said Bechdel, who first encountered Koren well into her own career, when she succeeded him as Vermont’s cartoonist laureate in 2017. (The ceremony involved the literal passing of a crown made of evergreen boughs.)

“This is someone whose work I’d read pretty much all my life,” Bechdel said. “It was kind of wild how open he was and how friendly and encouraging — and, especially as a lesbian of a certain age, I’m always nervous people are going to be homophobic or something, and he was so not that at all.”

The two became fast friends and would spend time together in his studio whenever possible. “I just loved talking comics with him,” Bechdel said. “That was just such a massive gift from the cartooning gods.”

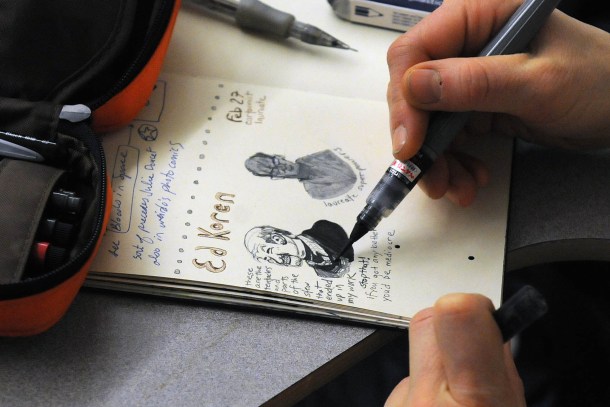

Decades earlier, the cartoonist Tim Newcomb had a similar introduction to Koren. Early in Newcomb’s career, in the mid-1980s, his work appeared in a Montpelier show alongside that of more established artists, such as Koren.

“I was just crosseyed to be in this show with this famous New Yorker cartoonist, and he couldn’t have been nicer,” Newcomb said.

Over the years, they and their families became close, vacationing in the Caribbean and spending Thanksgivings together. When Newcomb was feeling discouraged, he said, Koren would call or write and tell him to keep his chin up. “Ed was such an enthusiastic mentor,” Newcomb said.

He remains in awe of Koren’s work — populated by fuzzy, furry, toothy, nosey characters not dissimilar to the artist himself and, more often than not, based on those he’d observed in his native Upper West Side or his adopted home of Vermont.

“Ed, more than any cartoonist I can think of, had his own style,” Newcomb said. “You can see a Koren cartoon from across the room and there’s no doubt.”

His work, according to Bechdel, “is so idiosyncratic, so beautiful, so unlike anything that anybody else does. How he gets that effect was always so fascinating to me. His lines aren’t even lines. They’re like these little insect trails or something.”

Koren was “one of the most distinctive cartoonists that the New Yorker ever produced — right up there with (Charles) Addams, (James) Thurber and Roz Chast,” said Bill McKibben, the writer and environmental activist.

“He was the last, in a sense, of the great New Yorker cartoonists of his generation, and of that kind of unironic, un-stylized, just really funny gag cartoons,” McKibben said. “He could make me laugh every single time. What was greatest about them was there was always something generous and kind about them, too. It was people comically trying to do their best.”

McKibben was just 21 when he joined the staff of the New Yorker and met Koren. “He was incredibly kind to me from the start,” McKibben said. “If there was ever a person who exemplified the word ‘mensch,’ it was Ed in every way.”

Koren also “had an edge,” Bechdel said. “He did not suffer fools. When he saw bullshit, he would call it, and I loved that about him.”

He would, undoubtedly, have poked fun at the posthumous praise piled on him and saccharine remembrances such as this.

“Everyone’s talking about how sweet he was, but he could also be a bit of a curmudgeon — a winking one,” Mingle said. “He knew it and he played it up.”

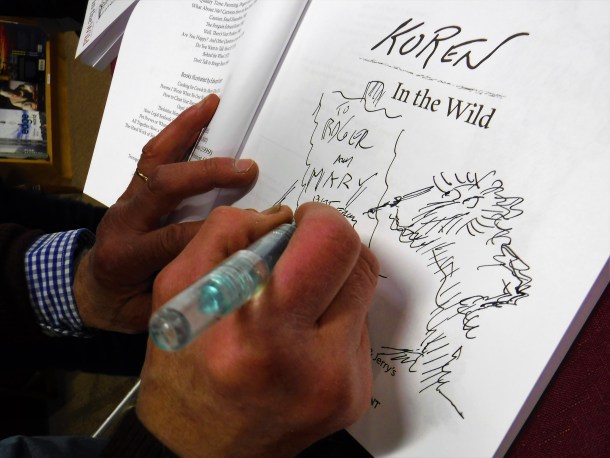

In Vermont, where Koren moved full-time in 1982, he was known for his many small — and sometimes not-so-small — generosities. He offered up countless drawings for T-shirts, mugs and posters to help community organizations raise money.

When Sturm helped establish the Center for Cartoon Studies, Koren was quick to lend his support. At a fundraiser he and Curtis held for the center — featuring a shredded coconut cake resembling a Koren character — Sturm observed the masses approaching the cartoonist.

“There were so many people who were, like, ‘Thank you for drawing that T-shirt for us,’” Sturm recalled. “There were just so many people touched by his work and touched by him.”

When Remnick sought to acquire a Koren drawing and insisted on paying him a fair price, the editor said, Koren insisted that Remnick instead cut a check to a Vermont school that had suffered damage in Tropical Storm Irene.

Longtime friends, such as the New Yorker writers Mark Singer and Calvin Trillin, accumulated many a Koren illustration over the years, often as a thank-you note or to celebrate a birth, a marriage or another decade of life.

“I realized the other day I have something by Ed in practically every room of the house,” Trillin said.

Singer met Koren in 1974 when the former joined the New Yorker staff. They hit it off right away and spent time together in New York and then Vermont — often running on the roads around Brookfield.

“Ed never stopped moving,” Singer said. “It was painful at the end when he was forced to slow down because he needed to be up and about every single day. So it was cross-country skiing, running, hiking. He did it for all the fitness benefits, and I think also as an antidepressant.”

Singer described Koren’s marriage to Curtis as “far and away the wisest thing he ever did.” Koren had been married before and had two older children, Nathaniel and Sasha. But in his 50s, after moving to Vermont, he and Curtis had their only child, Ben.

“He used to piss and moan, ‘I’m too old’” to be a father again, Singer recalled. “But he found out that he was not too old.”

According to Singer, Koren wanted nothing more than to live long enough to attend Ben’s white coat ceremony upon matriculating at medical school this fall. “I grieve that Ed missed out on that,” he said.

“I thought Ed would live forever because of how fit he was,” Singer said. “Ed only slowed down toward the very end, and I give Curtis enormous credit for that, because he was happy. Ed was surprised by that happiness, I think. I really do.”