“What time is it?” wasn’t always as straightforward a question as it might seem. That’s because up until the late 19th century, there was no universally accepted time. Every town had its own time, known as local time. Nearby towns could run on times that differed by minutes.

Those types of temporal discrepancies could even occur within a single community; the time on people’s clocks and pocket watches represented a mere approximation. And for centuries, it hardly mattered.

But things started to change in the mid-1800s. Life was speeding up, and business and science were demanding greater synchronization.

The Burlington Free Press joined the call for uniformity. “Have we not about reached the point where the adoption of a standard time would be a desirable thing?” the newspaper asked readers in September 1883. To illustrate the need, the paper cataloged the array of competing times in the downtown alone. “We now have railroad time, Unitarian church clock time, College street church time, the time set by the fire alarm signal at ‘about’ 9:15 every morning, and a separate time for each and every mill along the lake shore.”

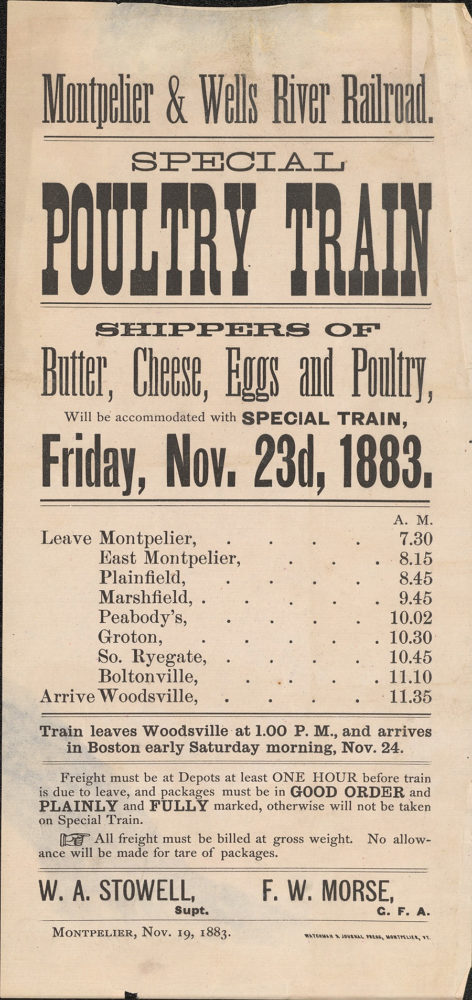

The main driver for standardization was the railroads. It’s hard to grasp just how much this new mode of transportation changed the world. Before the railroad, the greatest leap forward for speeding humans over land had come 6,000 years earlier with the domestication of the horse. The advent of trains, which could travel more than a mile a minute by the mid-1800s, shattered people’s sense of both time and distance.

Here’s why that mattered for how people kept track of time. The easiest way to set a clock is to do so at the midpoint between sunrise and sunset, when the sun is at its highest point in the sky. People have been able to mark noon, also known as “solar noon” and “local noon,” at least since the invention of the sundial more than 3,000 years ago.

You couldn’t set a clock down to the minute with this sort of technology, but in a slower-paced world it was good enough.

The thing about local noon, though, is that, well, it’s local. Move 15 miles east and noon will arrive 1 minute earlier; 15 miles west and it will arrive 1 minute later.

Again, if you aren’t moving very quickly, that doesn’t really matter. But trains run fast. They also run on tight schedules. And sometimes trains share the same bits of track, but in opposite directions, so they need to get their timing right. Minutes matter.

A head-on train crash in Rhode Island in 1853, which killed 14 people, was attributed to crewmembers misreading the railroad timetable.

You can hardly blame them for being confused. Railroad companies were publishing schedules based on what was known as “railroad time.” They typically chose the time used by a major city, based on its local noon. Observatories telegraphed time signals at noon to any business or municipality that subscribed to the service.

In the Northeast, Yale’s observatory signaled what was known as New York Time and Harvard signaled Boston Time, which was used by much of New England and was 12 minutes ahead of its New York counterpart. The Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., also provided time signals to much of the country. Many, though not all, Vermont rail lines ran on Montreal time. One exception was the trains heading east from Island Pond, which ran on Portland, Maine, time.

American railroad companies used 53 different times to set their schedules. Passengers needed to know how the time used by the train they were hoping to catch corresponded with their local time.

Railroad schedules clearly stated which time system they were using and newspapers occasionally printed charts showing the time difference between different cities, so passengers could make their calculations.

The confusion caused countless passengers to miss their trains, and occasionally led to railway workers making deadly miscalculations.

Living in a world where the local time was less a fact and more a matter of opinion caused some bewildering disputes. For years, two sets of bells had tolled the time in Rutland: the ones at the old Congregational Church and those at the county courthouse.

“There was for some time quite a rivalry between the different establishments having charge of the two clocks,” the Rutland Herald explained in 1870. “They did not seem to care in reference to whether or not they had the correct time, but only to keep the clocks apart.”

The two clocks differed by a full 20 minutes. The Herald reported that railroad workers protested when their bosses wouldn’t let them start work by the later clock and leave work by the early one.

The job of keeping public clocks in town correctly set often fell to jewelers, who were familiar with timepieces and motivated to advertise their utility. Jewelers sometimes subscribed to an observatory’s time service to ensure their clocks’ accuracy.

“Gibson, the jeweler, will furnish you with standard time,” the Richford (Vt.) Journal and Gazette reported in October 1883, adding: “(H)e keeps on hand a splendid assortment of standard timekeepers.”

During the early 1870s, railroads began discussing ways to coordinate their clocks. As part of this standardization, they considered a proposal to whittle the 53 time zones under which they currently operated down to just four, which would span the United States.

The arrangement didn’t require congressional approval; this was just a standard that needed to be set by a single industry. It was more than a decade before they settled on a final plan for how this would be done.

The new standard was set to go into effect at noon on Nov. 18, 1883, but many Vermont rail lines and communities adopted the standard six weeks early. The Central Vermont railroad implemented the new standardized time for most of its lines on Oct. 7, setting its official time back 12 minutes. The Vermont Phoenix newspaper explained the process: “At 12 o’clock noon on Sunday all telegraph offices on the several lines were open, the new time was given, and all railroad clocks and the watches of employees were set to correspond with it.”

The Middlebury Register urged its local community to use this opportunity to synchronize its local time with the railroads. “Would it not be well if the college, the high school and the town clock were run by the standard time?” the paper asked. “There has hitherto been a wide divergence, causing seemingly unnecessary confusion.”

Days before the new time standard was to be implemented by all American and Canadian railroads, the St. Albans Daily Messenger editorialized in favor of the move. “There can be no question that this innovation is a step in the right direction, because it does away with much trouble and inconvenience occasioned by differences of time,” the paper wrote. “The railway men have realized that they needed some common standard of time, not only for their own benefit but for the convenience of their passengers, and while some unreasonable opposition has been raised to the new system, it is probable that it will finally be adopted everywhere.”

It had already been adopted in railroad towns like St. Albans, with the Messenger reporting that “town time and rail road time here are one and the same.”

The new time standard technically governed only railroads, but community leaders were confident the advantages to businesses and the people at large meant any holdouts would eventually fall into line. “The smaller cities and towns will sooner or later, in the natural order of things, conform to local railroad time,” the Vermont Tribune of Ludlow predicted.

Not everyone was enamored with the new standard time. People who had to set their clocks forward complained that they had been robbed of minutes. And some people felt they had lost something else important: the link to the natural world (the connection between the sun being at its highest point and when their clocks marked noon). They wanted to return to what they called “God’s time.”

And in truth, under the new system, only a slender slice of each time zone experiences noon at true midday. The Maine communities of Bangor and Eastport went so far as to revert to local time, for a time.

But for a change that affected nearly everyone, the move went off without major glitches. Still, some adjustments had to be made. In Vermont, for example, setting the clock back meant the existing school schedule had classes ending at dusk, so Brattleboro and perhaps other communities moved up their start and dismissal times.

The Free Press informed its readers that they no longer would have to hear the seemingly random ringing of bells to mark the time. “The new standard time was taken at every railroad station in Vermont Sunday,” the newspaper explained. “In this city the clocks on the Unitarian and College street church towers were set by the new time; the clocks in the public schools and the 9:15 signal will follow the standard.”

Some people seemed to revel in the idea of having the official time, which must have felt like a thoroughly modern way of life. The Spirit of the Age of Woodstock described a man visiting town. “He came in from the country Monday, stopped in front of J.R. Murdock’s jewelry store, looked up at the sign of the big watch, pulled out his ‘turnip’ (pocket watch), set it, and walked off as straight as the seam in an ulster (overcoat), satisfied that he had the ‘standard time.’”

Postscript:

It wasn’t until 1918 that Congress officially adopted the railroad’s time system for the nation. Not every country has done likewise. Not until just five years ago, a full century after Congress accepted railroad time, did the Russian railroad system change. Previously it had run the entire system, which crosses a startling 11 time zones, on Moscow time.