Kayla Duvel is a reporter with Community News Service, part of the University of Vermont’s Reporting & Documentary Storytelling program. This story first appeared in The Winooski News, a Community News Service product, on Nov. 19.

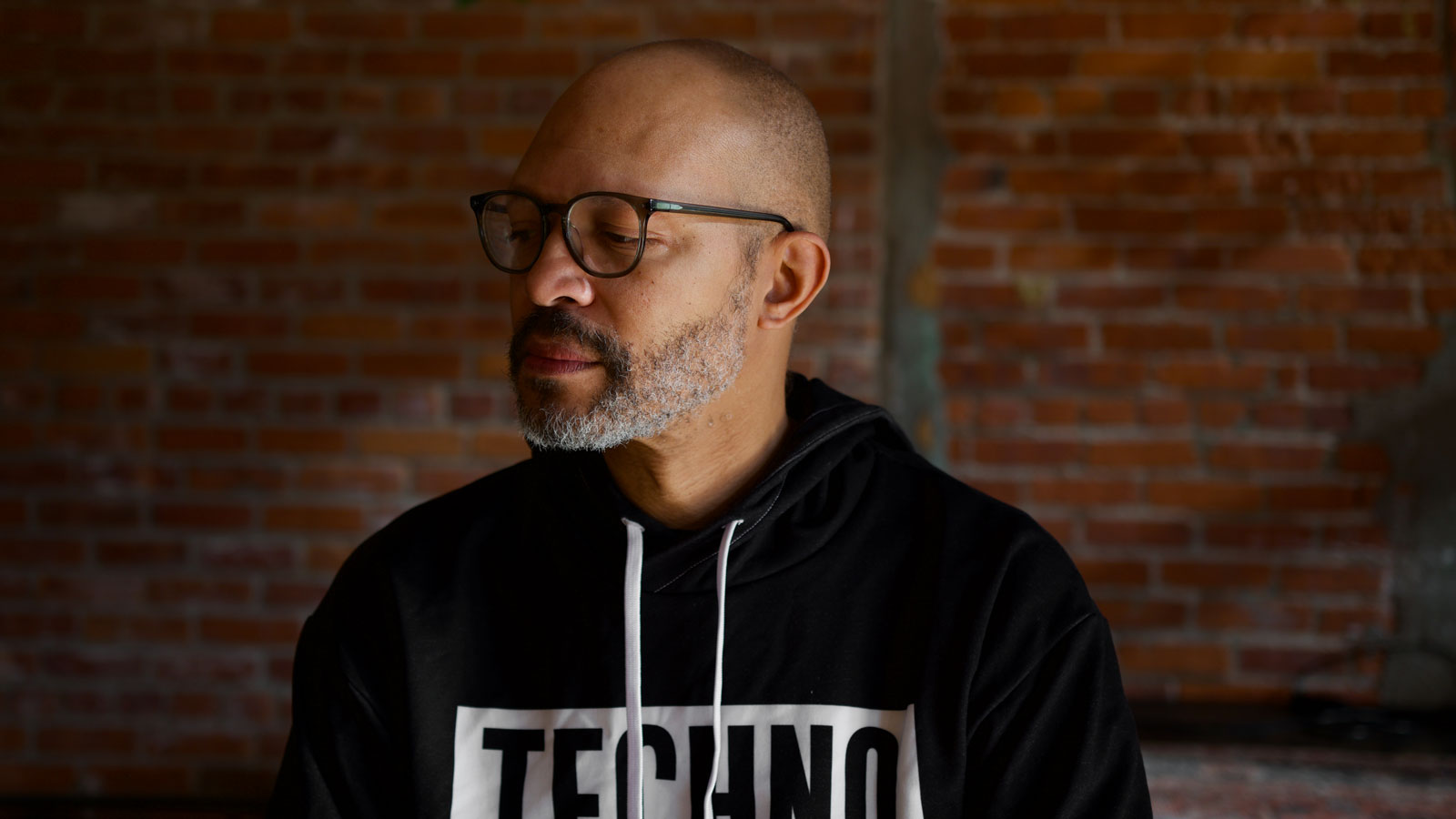

Craig Mitchell stands before Mount Kilimanjaro, flanked by a friend.

“You have to be ready for the mountain, and the mountain has to be ready for you,” says his friend, but Mitchell starts climbing.

The two ascend at record speed. But when the peak is in sight, Kilimanjaro erupts, sending scorching lava toward the travelers. “The mountain wasn’t ready for you,” his friend yells.

Mitchell, Winooski’s unofficial DJ laureate, has had the same recurring dream for nearly a decade. He calls it Craig Land, a realm where the terrors of the outside world keep him locked between the four walls of his house.

“Maybe that’s from my childhood, because outside was always dangerous,” the 51-year-old said. “It was very scary.”

That latest twist to the dream — finally venturing outside, only to be met with a raging mountain — seems like a metaphor for where the local legend finds himself now.

Mitchell has been playing gigs in the Winooski and Burlington area for more than 30 years. His musical career has taken him to New York City, Boston, Jamaica and Canada. He’s worked with Jay-Z, Janet Jackson, Yoko Ono, Backstreet Boys, The Strokes, Michael Buble and Moby.

But still he feels danger when he steps outside. He fears he won’t be accepted if he is transparent about his identity. He worries that expressing himself — letting people know about his traumas, his sexuality, the complexity of being a gay Black man — will put him at risk. Maybe he’ll become the target of harassment. Maybe his loved ones will be threatened. Maybe he’ll die.

So Mitchell performs. For his livelihood, for his life. But his dream has changed, and he has too. He’s no longer trapped in his Craig Land home. He’s trying to conquer the mountain and, in the real world, show people who he is inside.

But are they ready?

‘A lot of trauma’

He spins discs in clubs at night, but during the day Mitchell volunteers with HOPE Works, an organization that has a 24-hour hotline for victims of sexual violence. The work holds special value for him, he said, because he’s been sexually assaulted too.

Decades ago, relatives forced him and another young relative to wrestle, he said, “which would then turn into them watching us doing sexual things with each other.”

He described a particularly traumatic incident at a family party in which he begged people to believe his story, but no one did.

The way he views intimate relationships was further complicated later by several partners who Mitchell said raped him.

“It affected me in a lot of ways, and it still affects me, but my eyes are always open to make sure someone is safe,” he said. “It’s a lot of heavy stuff. A lot of trauma.”

So he looks to channel his past experiences into helping others feel comfortable.

He’s found that sense of safety for himself through performance.

“(In school) I wasn’t cool enough, I wasn’t Black enough, I wasn’t white enough, I wasn’t any of that stuff,” he said. “Inside (my home) was where I could put on my costumes and my mother’s wigs and my mother’s blue eye shadow and, you know, have fun and be safe, with the curtains closed.”

Often he’d put on living room performances after school while his mother was still at work.

One night, in between the outfit change for a David Bowie-inspired performance, Mitchell heard the back door open. His mother had come home earlier than usual, and Mitchell was outfitted in her green and blue floral dress, one of her wigs and her blue eye shadow.

“Craig! We’re going to the store,” she called. “Come get in the car!”

He rushed to put the wig away and hang the dress back up, then joined his mother in the family’s beat-up sedan.

He noticed her eyeing him in the rearview mirror.

When he finally asked what was up, she responded, “You know, I don’t mind you in my makeup, but that blue is just not your color.”

His mother was more accepting than he had thought, but she proved more of an exception to the rule.

The campus culture at Saint Michael’s College, which he attended in the ’90s, was infused with heteronormativity and homophobia.

He recalled a chant that would be cheered at parties after sporting events: “Drink beers, kill queers.”

During one spring break, when he worked as a DJ in Jamaica, people repeatedly threatened to kill him for being a gay Black man. Some broke into his house, followed him to work and yelled at him in the street.

For weeks, he said, he was harassed, targeted and assaulted by people angry at his existence.

The experience could have defeated him. Instead, he decided to be even more open about who he was. “I’m tired of being scared,” he recalled thinking. “I’m sick of this. If I’m going to die, I’m going to die right here.”

The people’s DJ

It wasn’t easy for Mitchell to carve a place for himself in society, but after DJing in the greater Burlington area for more than 30 years, he’s become known as a “community builder,” said Jim Lockridge, director of Big Heavy World, a music organization active in the Vermont scene since 1996, when Mitchell was first starting out.

“He programmed and hosted a live New Year’s Eve broadcast of people who reflected our local LGBTQ and BIPOC communities and gave them a platform on our radio station as part of the New Year’s celebration,” said Lockridge. “(In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic) he hosted multiple listening circles, virtually, of people who represented different genres and demographics from our music community.”

Mitchell is even the frontman of a Prince tribute band. The group performed a sold-out show at Higher Ground after the 2016 death of his favorite musician.

Time and time again Mitchell has taken his own traumatic experiences and flipped them to be positive vehicles for change. He helps create for others the bubbles of comfort he has always sought, and his ability to connect with people is clear in his success.

Mitchell is 12 years into a residency in one of the busiest nightclubs in Burlington, Red Square. “He’s a DJ for the people,” said Alexander Flamini, the club’s general manager, who has known and been booking Mitchell since 2008.

“He’s extremely intelligent and knowledgeable about current events and pop culture and music,” Flamini said. “He’s very easy to talk to and very personable, and that melds well with his shift at any bar because his persona transcends from merely entertaining and playing music (to that of) a showman.”

But even with plaudits from the Vermont music community and a wide-reaching fanbase around Chittenden County, Mitchell feels like few people know the real him — and often finds himself worrying something bad will happen to him if they did.

He recounted one incident from a few years ago in downtown Winooski that haunts him to this day.

During former President Donald Trump’s first election campaign, Mitchell felt racists were emboldened in spewing hate. It was in those days that someone called him the N-word for the first time in Vermont, he said.

“I was crossing the street, cars were stopped and this car revved its engine and gets right here,” he said, holding his arm a few inches from his torso to show how close the car was from his body. “And the guy screamed, ‘You fucking (N-word), hurry up.’”

“I’m looking at the car, and there are three people laughing, on their phones filming me, so they’re setting me up, making me look like the bad guy,” he said. “I kept walking, and it hurt my soul, but I kept walking.”

He hears the slur in his mind every time he crosses that street, he said, and he worries something like that might happen again — but violent this time.

“What if there’s another person next time who might hit me?” he asked. “When you say the word with venom, it’s a whole different animal, it cuts like a knife. Literally it was like I was 5 years old again.”

Escaping the box

Mitchell shows little of what’s weighing on his mind to the crowds at his shows.

“His charisma and stage performance and connection to the crowd is unmatched in town, in Burlington and the DJ community,” said fellow area DJ Evan LeCompte, who goes by DJ Cre8 and credits Mitchell for influencing the types of tracks he plays in sets.

Mitchell said he finds meaning in helping audiences let loose. The performances are a catharsis, in a way. “It’s all for the show, and that’s a big part of who I am — the show — it fills me up,” he said. “I’m a giver.”

Robert Rapatski, the former owner of the now-closed Zen Lounge venue, described Mitchell’s stage presence as fearless, the kind of fully invested showmanship few DJs come close to.

“He brings this energy that makes you want to be there — it makes you want to be involved whether as a listener or as a person dancing or as just a person observing or performing with him,” said Rapatski, a close friend and former business partner of Mitchell’s. “He makes you want to be there and be part of it.”

When he performs, Mitchell sees people reach some sense of freedom and break free from the “tiny little boxes” the world puts them in. He wonders how many of them go back to their daily lives inside those boxes after the show. They remind him of himself in that way. But he wants to fully escape those boundaries.

In his dreams, Craig Mitchell is finally ready to climb the mountain and face the perils of the world. In real life, he’s ready to show people who he truly is.

He’s just waiting for everyone else to catch up.