BENNINGTON – In a one-story house a few blocks from downtown Bennington, Mary Jan spends several hours a week fashioning brightly colored yarn into winter scarves or bath mitts. Her hand-knit creations are sold at a couple of stores in the county.

Two days a week, she also works at a local food manufacturer, helping make packaged snacks.

Mary Jan, 35, is still getting used to earning an income. Until August of 2021, when her family fled Afghanistan, she’d been a stay-at-home wife and mother of three. Now, her part-time jobs fill some of her free time, but most importantly, they augment her husband’s salary as the family builds a new life in America.

“It’s really good that I can get some money out of this,” Mary Jan said of her knitting, speaking in Dari through an interpreter. “Because the U.S. is really expensive, one person cannot afford what a family needs.”

Her husband Mohammed, 45, is employed as a carpenter by an independent contractor in the county. He previously served as a security guard at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul for nearly a decade.

The family decided to leave their native land, fearing for their safety as the Taliban advanced into the Afghan capital in August of last year. Because of his American ties, Mohammed was afraid the Taliban would throw him into prison.

The couple and their 13-year-old son are among at least 76,000 Afghans who’ve been evacuated to the U.S. since the American military completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan on Aug. 30, 2021.

“I was happy that I’d be able to get my family out of there,” Mohammed said in Dari. He asked that VTDigger not disclose the family’s full names to protect the safety of relatives who are still in Afghanistan.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Afghans now constitute one of the largest refugee populations in the world. The vast majority of Afghan refugees — 2.2 million — are living in Pakistan and Iran.

The UNHCR noted that some of the Afghans who’ve relocated served as translators or interpreters during the U.S. mission in Afghanistan. Due to their employment with the U.S. government, many faced serious threats to their safety.

Approximately 260 Afghan adults and children have been resettled in Vermont. They include eight families in Bennington County, according to the Ethiopian Community Development Council, a federally contracted resettlement agency that has placed Afghan refugees in Windham and Bennington counties.

Crucial community support

Mohammed’s family is adjusting to local life with the assistance of volunteers — area residents who help the Afghans navigate tasks, such as finding a home, getting a job, learning to drive, setting up doctor’s appointments and learning English.

Most of the volunteers here come through Bennington County Open Arms, a volunteer organization that four residents set up last year to support international arrivals in the county.

The resettlement agency has so far placed 28 adults and children in the county, in towns such as Bennington and Manchester, said Bennington County Open Arms director Anandaroopa, who goes by one name. The organization has 35 core volunteers and is always looking for more.

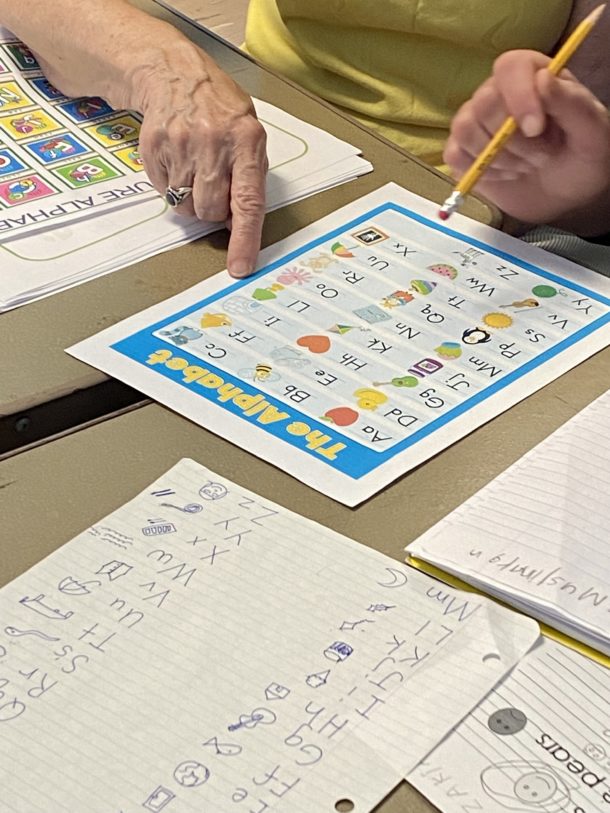

One morning this summer, Mary Jan joined a handful of fellow Afghans participating in twice-a-week English classes at a church facility in Bennington. The classes are co-organized by Bennington County Open Arms and The Tutorial Center. The organizations hire professional teachers for the classes and also sign up volunteer tutors.

That day, as is their routine, teachers grouped students according to their English level. One class dissected the elements of a complex sentence on a blackboard while, in another room, Mary Jan wrote and recited the English alphabet.

She and Mohammed had said their unfamiliarity with English was a big hurdle in adapting to the U.S. Their teenage son, Shahed, on the other hand, is picking up the language fast. He goes to the local middle school and attended two soccer camps this summer.

Mohammed, like the other Afghans who can’t attend the English classes because of work, get one-on-one lessons from volunteer “conversation buddies.”

“There’s a chance for people to make a difference,” said Tracey Hitchen Boyd, a volunteer who lives in Cambridge, New York, about half an hour away from Bennington.

Since February, she has assisted multiple Afghan families in various roles: as a conversation buddy, driving them to appointments, getting official documents such as social security numbers.

Leslie Kielson is a Sunderland resident who often helps the Afghans find jobs. She considers her volunteer activity as a way of repaying them for working alongside Americans in Afghanistan.

“These are folks, who, in many circumstances, risked their lives for this country,” she said, “and they’ve been just uprooted.”

A local business owner, Kielson said she sees the Afghans as “incredibly motivated to work,” since most of them also need to regularly send money to relatives back home. She said they’re “tremendously grateful” for the ways they’ve been welcomed to Vermont.

Carving out new lives

Abbas Ali, 46, moved to Bennington in the summer of 2021 after a few months of living in Albany, New York.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees brought him to the U.S. from Indonesia, where he’d been stranded since 2013 after fleeing Afghanistan. A native of Pakistan, he went to Kabul in 2011 after a suicide car bomber destroyed his residential neighborhood. He’d hoped Afghanistan would have better prospects because of the U.S. presence there.

An artist back home, Ali now works as a sales manager at a convenience store in Bennington. He lives with two co-workers in a trailer home in town and dreams of soon finding his own place, which would double as his art studio.

One morning before heading to work, he laid out three unfinished paintings, which he described as created in both watercolor and miniature art style. He said they’ll become part of an exhibit to raise money for refugees in Indonesia — once he gets around to completing the pieces.

“I was in the middle of the third one, then I had to come over here and start work,” said Ali, who speaks English fluently. “I could not find the time.”

Bennington County Open Arms is helping him find a new home. As with the other Afghan arrivals, the organization will also help him source furniture and other household items.

Ali is currently focused on making a good living, so he can bring his wife and two teenage children to the U.S. They’re still living in Pakistan, and he hasn’t seen them in 10 years.

He said his children, now ages 16 and 13, have to be prodded to speak with him on the phone. His relationship with his wife has also become increasingly strained due to the passage of time and their distance.

“I’m desperate to see my family,” he said. “The only thing I can do is to work really hard, really hard to at least show the government, the state that … I can sponsor my family.”

Mohammed and Mary Jan are facing similar stressors.

The couple is working to bring to the U.S. their two other children who got left behind in Afghanistan. As the family made its way into the Kabul airport to get on a flight bound for the U.S. last year, the two boys got separated from their parents amid the crush of people trying to flee. They were able to safely return to relatives.

Mary Jan talks about having “an empty space” inside her heart as she waits to be reunited with her children.

Mohammed said he enjoys the greater freedoms of living in America, but he often finds his thoughts straying to his two sons who are an ocean away.

“Even when I’m working, my mind is still back home,” he said. “Once they come over here, we’ll be more settled and happier.”