John “Bud” Fowler might be the most important baseball player you’ve never heard of. The Baseball Hall of Fame hopes to rectify that this summer when Fowler is posthumously inducted into this prestigious institution, celebrating him as one of the greatest players of the game.

A gifted pitcher, skilled fielder and hitter, and brave baserunner, Fowler cobbled together a stellar career during baseball’s bleakest period, when team owners colluded to bar Black players like Fowler from the top leagues. Rampant racism and the financial instability of many clubs forced him to move from team to team to find work. During his 13-year career, he played for at least 18 different franchises.

Fowler was a trailblazer. He is believed to have become the first Black professional ballplayer when he signed a contract in 1878. Nine years later, Fowler became the first Black player to captain an otherwise all-white team. He earned that distinction during a brief but remarkable stint playing in Vermont.

Though he started his career as both a pitcher and a catcher, Fowler was even more versatile than that. He excelled at other positions, particularly second base.

Off the field, Fowler demonstrated a creative baseball mind and a talent for promoting the sport, helping organize Black baseball teams and leagues, as well as “barnstorming” squads that traveled the country.

He had an excellent eye for talent and knew the best Black players in America. A nod from Fowler was often enough for a team to sign a player. A fellow player called Fowler “the celebrated promoter of colored ball clubs, and the sage of baseball.”

Fowler grew up in Cooperstown, New York, now the site of the Baseball Hall of Fame, so his July 24 induction will be something of a homecoming. Bud Fowler was born John W. Jackson, but changed his name later in life. Some historians believe he wanted to hide his baseball career from his family.

His father, who had escaped slavery and become a barber, had trained his son to follow him in the safely middle-class profession. Fowler might have worried his family wouldn’t approve of his pursuit of a career they viewed as less stable and reputable.

“There is a perception that baseball in the late 1800s was friendly and polite,” says Tim Hagerty, a baseball announcer and historian of the sport, who wrote about Fowler recently for the Society for American Baseball Research. “But this was really an era of ballplayers fighting and doing whatever they had to to win.”

Players were poorly paid, Hagerty notes, and had to take offseason jobs. Fowler sometimes worked as a barber.

Fowler had a habit of calling his teammates “Bud.” Maybe it was easier than learning everyone’s name, given how many teams he played for. It’s a habit shared by one of his fellow 2022 inductees, David Ortiz of the Boston Red Sox, who said he met so many people he just started calling new acquaintances “Papi,” which is Spanish for “Daddy.” As with Ortiz, the name Fowler doled out to others stuck to him too.

Beating Boston

Fowler’s break into pro ball came in the spring of 1878, when at the age of 20 he pitched in an exhibition game. His amateur team from Chelsea, Massachusetts, plus a few other skilled players, took on the reigning National League champions Boston Red Caps. (The team would later move and eventually become the Atlanta Braves.)

Fowler wasn’t overawed by the occasion. He allowed only three hits as his team beat Boston 2-1. His performance drew the attention of a team in Lynn, Massachusetts, which then gave him his first professional contract. The deal was historic, making Fowler the first African-American professional baseball player, and therefore also the first to integrate a professional team.

Fowler’s career is difficult to track. Baseball records were notoriously spotty during this era. Games were usually reported in newspapers, but no one compiled players’ statistics. That job has fallen to baseball historians, who have pieced together Fowler’s peripatetic career.

After joining Lynn, Fowler played for teams in Worcester and Malden, Massachusetts. In 1881, he was playing for a team in Guelph, Ontario, but left when some players objected to having a Black teammate. He briefly pitched for the Petrolia Imperials, another Ontario team, before playing for, and sometimes also managing, a string of all-Black teams: the New Orleans Pickwicks, the Black Swans of Richmond, Virginia, the St. Louis Black Sox, the Niles Grays of Youngstown, Ohio, and the Stillwater team in Minnesota.

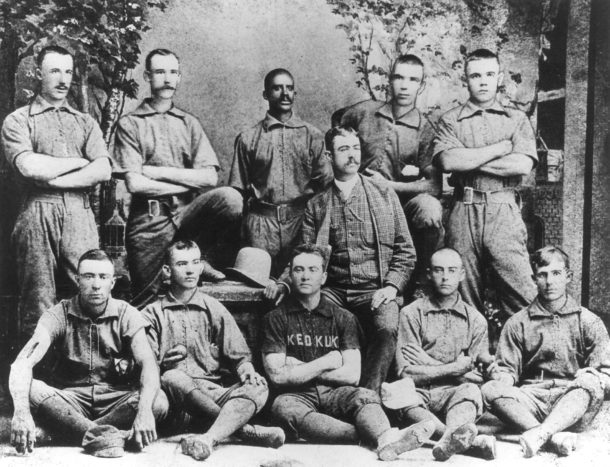

The next season, 1885, he traveled around the country as he played for three different teams — Portland, Maine; Keokuk, Iowa; and Pueblo, Colorado. Despite his constant relocations, Fowler performed brilliantly.

That year, The Sporting Life, an important 19th-century baseball publication, wrote of Fowler: “With his splendid abilities, he would long ago have been on some good club had his color been white instead of Black. Those who know say there is no better second baseman in the country.”

Wooden shin guards

The racism Fowler faced was pervasive, says Hagerty, who as a baseball historian was drawn to Fowler by his life story and their shared connection with Vermont. Hagerty graduated from Lyndon State College and was the first announcer for the Vermont Mountaineers, a collegiate summer league team in Montpelier. He now announces games for the El Paso Chihuahuas, the San Diego Padres’ Triple-A affiliate.

Hagerty learned that Fowler used to wear wooden shin guards when playing second base. According to an opposing player, Fowler “knew that about every player that came down to second base on a steal had it in for him and would, if possible, throw the spikes into him.” Baseball fans often yelled racial slurs at Fowler. Even umpires got into the act — one admitted to deliberately calling close plays against Fowler’s team.

“It is amazing to think of how in city after city before Montpelier, he was facing this racism and he never quit,” Hagerty says. ‘He just kept going.”

The worst came in 1887, when organized baseball banned Black players from the top leagues. The ban would hold for 60 years, until Jackie Robinson began playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

According to some historians, the event that sparked the so-called “color line” involved Fowler, who was then playing for a team in Binghamton, New York. On June 27, nine of his white teammates sent a telegram to team directors, threatening to go on strike if Fowler and another Black player, William Renfro, weren’t dropped by the team. The directors caved to pressure and released the two players.

Looking for work, Fowler signed in early August to play for Montpelier of the independent Northeastern League, informally called the Vermont State League, which also included teams from Rutland, St. Albans and Burlington, as well as a team from Malone, New York.

Welcomed in Montpelier

Historians can only guess at the lived experience of historical figures. Contemporary observations offer clues, however, and evidence suggests that in Montpelier, Fowler found a supportive and enthusiastic fan base and press. Reporting on his first game, the Aug. 6 contest against St. Albans, the Argus and Patriot of Montpelier wrote: “(B)ase ball enthusiasts of the town were treated to as pretty a game as they could wish for.” The paper singled out Fowler for praise: “(T)he man who covered himself with glory was the recent acquisition of the Montpelier team, John Fowler, colored, of New York city. He played a great game at second base. … A brilliant double play in the eighth inning won him a storm of applause.”

Sportswriters often mentioned Fowler’s race in describing him. He was the league’s only Black player. He was also clearly one of its best.

“(Fowler) captured the crowd by his fine playing,” the Burlington Free Press reported on Aug. 15. The next day, the Free Press summarized another game by writing that “(t)he features of the game were the batting and base-running of Fowler.” And the day after that, the Montpelier Argus and Patriot commented on the “remarkable manner” in which Fowler played second base. “Not a ball that came in his direction passed him, and he made a double play which brought forth prolonged applause. A running high jump and left-handed catch of a fly also elicited much praise.” The fact the newspaper mentioned which hand he caught the ball with suggests Fowler played barehanded. Gloves were just coming into vogue and were far from universally worn.

Vermont baseball fans knew of the appalling treatment of Fowler in Binghamton. On its front page, the Vermont Watchman and State Journal of Montpelier excerpted a story from the Boston Herald about the white players’ threatened boycott. The Watchman followed that by commenting on the players’ motivation: “Considering (Fowler’s) superiority as a base-ballist, it is reasonable to suppose that jealousy and not prejudice against color influenced the weak fellows of the Binghamton club.”

The Argus and Patriot also took the opportunity to mock the New York team: “If Binghamton or any other club has any more Fowlers, Montpelier can find a place for them, for he can ‘play ball.’ ”

“That to me is the most amazing thing about Bud Fowler in 1887,” Hagerty says. “In late June, his white teammates sign a petition and refuse to play unless the team gets rid of this player. Then just two months later and in pretty much the same geographical area, Fowler has a completely different experience.”

Newspapers sometimes referred to Fowler by what is, to modern ears, a troubling term, “mascot.” Referring to people of color as mascots has been called out as racist. It is unclear, however, how contemporary sportswriters and fans meant it in referring to Fowler. He was an indispensable part of the team and seemingly its best hope for victory.

Since the word “mascot” was being applied to an actual player, it is possible it had a meaning akin to the word “talisman,” which is often applied by British soccer journalists in reference to a team’s key player.

A week after newspapers announced his signing by Montpelier, they started using another way to refer to him: “Captain Fowler.” It is unclear whether he was chosen by team management or by a vote by the players. Fowler was the only Black player to captain an integrated team during the 19th century.

The new position suggests that Fowler had the respect of teammates and the teams’ owners. The Argus and Patriot noted that “(t)he management of the Montpelier base ball club have at least one thing upon which they can congratulate themselves, and that is that there appears to be no race prejudice among the players.”

According to Hagerty, Fowler’s new position, as one of two co-captains, would have had an array of responsibilities, including setting the team’s lineup and helping schedule games.

Fowler was also a leader during games. People noticed not just the quality of his play, but also his drive to win. “The game is ours; all we have got to do is bat it out!” a Free Press reporter heard him tell teammates.

Alas, Montpelier didn’t have more players like Fowler. The squad lost most of its games, and far too much of its money. The team folded before the season ended, and the rest of the league did likewise at the end of the season.

Researchers have to rely on newspaper box scores to compile statistics for the late 19th century, though not every game was reported. In the Montpelier box scores he could find, Hagerty calculated that Fowler had a stellar .429 batting average and stole seven bases in eight games. Fowler finished the 1887 season playing for a team in Laconia, New Hampshire, and played another eight seasons before moving into baseball management with Black leagues and individual teams. Fowler died young, at age 54.

In a career blighted by racism, the demise of the Montpelier team in 1887 was a particularly cruel twist for Fowler. “All the evidence is that this guy was beloved in Montpelier,” Hagerty says. “It seemed like he had finally found this place where people loved his skills on the field, but also treated him well as a person.”