Editor’s note: This story about the economic impact of the defense industry in Vermont is the first in a series.

In recent debates about the impacts of bedding F-35A fighter jets at the Burlington International Airport the arguments in support often come down to balancing noise and other impacts against economic necessities and benefits.

“One of my fears,” Lt. Gov. Phil Scott said at the start of the recent Air Force public hearing on the F-35 Environmental Impact Statement, “is that, with all of the talk at the federal level about reducing costs, if the program is not located here, there is a real chance the base could be reduced in size or possibly closed altogether.”

“This would have a profound impact on the City of South Burlington, the Chittenden County region, and the state as a whole,” Scott warned. “And it’s not just the 400 (National Guard) jobs; it’s the ripple effect as well.”

Opponents of the F-35s dismiss such speculations as a scare tactic that ignores the real costs.

Kelly Devine, speaking for the Burlington Business Association, made a more positive argument on the same evening: The Vermont Air Guard is a magnet that attracts more investments to the state’s thriving aerospace industry.

Chamber of Commerce speaker Christopher Carrigan liked the reasoning, but added an instructive point. Despite playing a significant, in fact diversifying role in Vermont’s economy, in part due to its military ties, he said the aerospace and aviation industry operates largely “under the radar screen” much of the time.

That makes it sound something like the much-maligned aircraft at the center of the current debate – expanding, multi-functional and yet engineered for stealth. Some people believe the F-35 will work when it counts. Others think it should basically be scrapped.

Originally, the F-35 was going to replace the F-16 as a jet fighter. But stealth missions and air support were added as the needs of various military branches, and potential foreign buyers, altered the plane’s design and mission. Eight other countries have agreed to buy the plane — whenever it’s ready. But various agencies and officials have decried repeated cost increases, design faults and missed deadlines.

Whatever the outcome of this most expensive product launch in aviation history, the debate in Vermont has already raised questions about the economic impact of military spending and whether the economy – or National Guard operations – will take a hit if, for some reason or other, the F-35s do not arrive.

Possible ripple effect on the aerospace industry?

A report commissioned by the Aerospace Industry Association recently concluded that aerospace and defense accounted for $1 billion in direct Vermont revenues in 2010, along with $5.7 million in business taxes, and 2,852 jobs with an average wage of $71,082.

What about the ripple effect? That depends, of course, on which ripples you choose to track. In terms of Department of Defense jobs, for example, Vermont ranks at the very bottom, just above American Samoa and the Virgin Islands. Civilian defense employee salaries are a surprisingly small $18 million. In procurement and military sales it ranks 47th.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement, which is under review until June 20, basing 18 of the new fighter jets at the airport in South Burlington would have no measurable impact on regional employment, income or the regional housing market. But 24 would translate into 266 more military jobs and another $3.4 million in salaries.

What type of jobs and whether Vermont residents will get them are separate issues to be addressed later in this series.

Under either scenario, about $2.3 million would be spent by the feds on modifications needed to accommodate the new aircraft. That would mean some construction jobs, albeit temporarily.

Aerospace, $2 billion-a-year industry in Vermont

The engine of Vermont’s military sector is aerospace, aviation and related manufacturing operations. According to the Vermont Aerospace and Aviation Association, a division of the Vermont Chamber of Commerce that represents about 250 members, the industry currently provides or supports more than 9,000 jobs, and generates around $2 billion in economic activity a year.

Chittenden County has received $6.3 billion in military contracts over the last 12 years, or 84 percent of the total.

Whatever the precise size of this ripple the fuel powering it is thousands of federal contracts signed and executed between the U.S. Department of Defense and private enterprises large and small. In 2011, Vermont-based businesses handled more than 1,600 contracts worth $621.3 million, down from $827 million the year before.

Between 2000 and 2011, Vermont businesses brought in a total of more than $7.5 billion in federal defense funding, according to government data compiled at governmentcontractswon.com. There were more than 12,000 separate contracts valued from a few thousand bucks to tens of millions. They went to more than 650 businesses across the state, although two corporations received, depending on the year, between 70 percent and 95 percent of the money.

The only Vermont county without a defense contract is Essex. The overwhelming leader now and for decades is Chittenden County, which has received $6.3 billion in military contracts over the last 12 years, or 84 percent of the total.

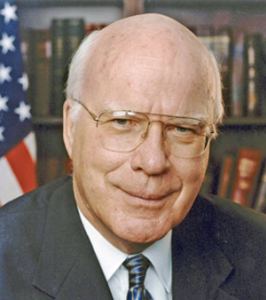

Leahy’s mission and Bennington’s comeback

In 2009, despite the global recession, Vermont firms actually saw a modest increase in defense revenue, almost $800 million in 1,467 separate contracts. As usual, the big winners by far were General Dynamics with $599 million and Simmonds Precision with $93.8 million, about 87 percent of the total that year. The rest of the contracts were modest by comparison and often won by companies not solely engaged in defense-related work.

Bennington became a special focus during the year. In August Sen. Patrick Leahy visited to celebrate a projected $1 billion Army deal with Plasan North America and its partner, the Wisconsin-based Oshkosh Corp., for thousands of all-terrain armored vehicles. Leahy had pushed hard for it during the budget negotiations and wanted to share the news personally.

“This is not a make-work program in Bennington, as much as I’m delighted to see the jobs that are going here,” he told managers and employees gathered at work for the occasion. An imposing all-terrain vehicle was positioned behind him. “This is a patriotic mission,” Leahy said. “This is going to save our sons and daughters, our friends, our family overseas.”

The program was the M-ATV, a smaller version of the mine resistant ambush protected vehicle (MRAP) being used in Iraq and Afghanistan. The goal was more speed plus safe negotiating of difficult terrains, without compromising Plasan’s armor. Once the first 2,244 armored M-ATVs were successfully delivered the Army ordered 1,700 more. It looked like a local manufacturing comeback.

Prior to this time Bennington companies had won $4.9 million in military contracts in the previous nine years. In 2008 the Bennington Microtechnology Center’s receipt of $1.3 million for research and development work was a highlight. Since 2008, however, Plasan has won at least $17.2 million and launched a workforce education project in cooperation with Community College of Vermont, training and offering certification for new employees.

Leahy returned to Bennington in 2010, this time to celebrate a $2 million research contract for Energizer. He also visited a composite plant, pledging help for a “cluster” of companies involved in development and manufacturing of lightweight composite materials that are used for aerospace and medical industry parts.

At Energizer Leahy explained how he secured a Pentagon research and development contract for the company: He had exploited his seniority, he explained, as the second-most senior member of the Senate, a member of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, and also on its Defense Subcommittee.

Early in his career, Leahy recalled, he was against the Senate’s seniority system and the influence it conferred. “I went home and said to Marcelle, ‘Terrible system, the seniority. It should be changed,’” he recalled.

Then the punchline: “But having studied it, I understand it a lot better.” The point? Maybe that having the advantage isn’t so bad if you know how to handle it and have the right cause.

One thing is clear. Leahy is extremely proud to be known as a player in Washington who “goes to bat” for jobs and developing businesses across the state, he explained. It boils down to working the committee and seniority system, extracting contract commitments from the Department of Defense and other federal agencies for the Vermont firms whose projects make sense to him.

In this case the goal was to help Energizer develop a high-power, ultra-lightweight zinc-air battery, initially for the military. Leahy called it the “next-generation power source” for soldiers. There was no guarantee that the research would be done locally. The main goal was to secure money for multiple years to manufacture it. Although being funded through military R & D money he also stressed that the battery had potential for civilian uses and could lead to more private sector jobs later on.

Although Leahy has not spoken about the F-35 or appeared at an aviation industry event lately, back in January 2011 he was proud to take credit for saving an F-35 program that would benefit the General Electric plant in Rutland. The Pentagon wanted to kill funding for an alternate engine. Leahy had the money restored in the budget bill and convinced the Pentagon to go along.

Critics called the alternate engine pork barrel spending. Leahy responded with a General Accounting Office study that said making development and production of the engine competitive would ultimately save $20 billion.

Contractors run the gamut

Vermont’s gross domestic product was $26.4 billion in 2011, placing it globally between Jordan and Latvia – with far fewer inhabitants than either. It has the smallest economy of any other state and is 45th in land area. In 2010 it ranked last among the states in gross domestic product and 30th in GDP per capita.

But there are advantages to being small. For example, Vermont consumes less energy than any state except Alaska and Connecticut, has less violent crime than most places, and has not become as dependent as other states on federal defense spending.

In “boom” times, defense work sometimes represents 5 percent of total state GDP, but usually contributes between 2 percent and 4 percent. By comparison, military contracts in South Carolina normally represent at least 6 percent of GDP, while Oklahoma’s five military bases contribute 7 percent, a $9.6 billion total that includes $5.6 billion in annual wages. Less dependence on defense revenues can translate into less job disruption during periods of downsizing for a volatile industry.

In the last dozen years, growth in defense contract dollars coming to Vermont has been steady, starting off modestly at $211.4 million in 2000, peaking at just over $1 billion in 2006, and leveling off at between $621 million and $827 million annually since 2008. In addition to financing small arms manufacturing at General Dynamics and aircraft parts production at Simmonds the contracts pay for development and manufacturing of missile and explosive components, guns, ammunition and “quick-reaction” capability equipment.

In some cases products have more than a military use. In Burlington, Problem-Knowledge Coupler has received $82 million in Defense department funding to produce “clinical decisions support technology” that helps doctors and patients make more informed decisions. In Winooski Preci-Manufacturing used almost $27 million for precision components used in planes, helicopters, ships, submarines and armored vehicles. Williston-based Triosyn, which received $33 million for work on eyewear and antimicrobial masks, has also been featured in an ad for Leahy.

Northeast Kingdom companies, mainly in Newport, St. Johnsbury and Lyndonville, have received about $200 million in the last 12 years. However, half of that total went to one company, Mine Safety Appliances, in 2004. Leahy visited Newport in 2010 to announce a $21 million contract for Mine Safety to produce advanced combat helmets for the U.S. Army. But last year only $134,000 in funding for that project was posted.

In central Vermont, several enterprises in Barre, Northfield, Montpelier, Randolph and White River Junction attracted around $100 million. The regional leader was Concepts ETI with $44.4 million in contracts for “measuring and controlling” devices. The company got $3.3 million last year. Norwich University and its Applied Research Institute have received more than $27 million. Hawkeye International in Hyde Park recently won $1.9 million for electrical equipment and components.

The center of Vermont’s defense industry is the Champlain Valley. Five of the 10 top defense contractors are located there, and Simmonds Precision is in Vergennes. Dozens of other businesses have contracts to provide support services, including moving companies, music and home furnishing stores, and an architectural firm. In addition, UVM has won 37 Department of Defense contracts worth at least $6.3 million.

The region currently gets more than 90 percent of all defense money coming to Vermont, up from 83 percent a few years. In other words, the work has diversified but more is being sent to the dominant part of the state.

Burlington leads with more than $5.3 billion in contracts since 2000. General Dynamics is followed distantly by Problem-Knowledge Coupler and Barer Engineering. South Burlington businesses brought in $55 million, almost half of that going to Pizzagalli Construction.

Williston companies received more than $100 million. The big year was 2005, which brought $44.5 million. Dew Construction received $40 million. Others leading contractors included Total Temperature Instrumentation with $6.6 million, Velan Valve with $4.1 million, and H & M Industrial Sales with $6.6 million. Microstrain, which produces sensors, received $11.5 million, and Triosyn has been awarded $5 million since 2009. Both companies added employees after winning contracts.

Businesses in Colchester received $5.8 million, but revenues dropped dramatically after a modest peak from 2003-2006. Up to 30 small contracts were signed a year. The largest were $2.3 million to Green Mountain Radio Research and $1.8 million for Montek Technologies.

Rounding out the regional picture is Essex Junction, not often a destination for defense contracts but gaining ground since 2000 with $25 million. Revision Eyewear has received $7.3 million in the last few years. The top recipient was Stewart Construction with $16.7 million, mostly received in the last two years.